The Holy Terrors for A Black & White Still Winter.

I'll be going back and once again seeing Cocteau's Orphic Trilogy this week, and I thought it might be fun in preparation for that to visit with one of his "eariler" works. Les Enfants Terribles was Cocteau's novel from 1929, a story he held quite close to him, refusing several times to bring it to the big screen until somehow Jean-Pierre Melville got the right to direct the film in '51. The two artists were well acquainted. Cocteau is said to have not left the set that Melville was supposedly in charge of directing. In fact, many people think Les Enfants Terribles was directed by Jean Cocteau -- it seems much more fair to note it as a collaboration between two very different filmmakers in the nature of what and how they approached their works.

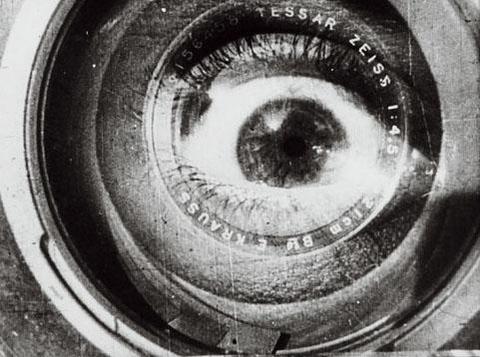

Criterion brought what they did to life on DVD in 2007, and one can look here for a good comparison, a reason to keep loving Criterion.*

Still, it's not an easy film to watch, no matter how beautiful Criterion made it with their restored digital transfer. When one tries to immediately describe Les Enfants Terribles, they are forced to describe a brother and sister, constantly craving each other's attention, constantly screaming at each other and in general being bratty toward all -- and some kind of incestuous overtone that must be either more directly present in Cocteau's book or better inferred by more understanding critics, because it's something I'm just not seeing after my first viewing.

I will remember this as the film that slowed down my winter black and white viewings because it took me over a week (maybe longer) to actually get through it. I started it several times but just couldn't stand these bratty kids.

It might have been easier if I really believed they were kids. I don't know what the ages of the actors were, but I am going to guess twenty-four for Edouard Dermithe, who plays the brother, Paul, and early thirties for Nicole Stephane, sister Elisabeth -- both in the script are supposed to be around seventeen. (Wow. I just looked these actors up. They are both now passed away, and were very close to the ages I guessed them in the film.)

They simply don't look like teens.

Even so, the teens from the story act more like bratty little Junior Highers. Perhaps the entire story should have been written for, and acted by twelve year-olds. (I have nothing against twelve year-olds in general, I simply think the story could have been better pulled off with this age-range.)

This is normally the point at which I would describe a plot, but honestly I think I've said enough to give an apt description.

The film is also terribly narrated by none other than Cocteau himself. I believe the narration in French is more poetic sounding, otherwise I have no idea why this dry sounding narration drifts in and out of so many scenes -- unnecessary, redundant, and drab.

A lot has been made about how Les Enfants Terribles pre-dated and influenced the French New Wave -- Melville being a somewhat transitional figure that would eventually shift to Godard. This is something I'd need to have better explained to fully understand, and I guess if this shift is true it explains why a film like this is still respected to this day and worthy of notice by Criterion.

But I felt about it much the same way I felt about Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, a film from 1966 which critics and cinephiles find important enough to continue talking about -- nonetheless a film which makes me wretch. I understand that a part of life is spending time with bratty people, but there are certain films which lack the redemptive quality I personally need in order to invest my time in them.

I attempted this film several times, and now I can't even remember whether or not I finished it.

All I know is that I'd never want to spend even an hour with any of the brats present here.

* When I think about the people at Criterion in charge of cleaning up and transferring old films and such, I typically get all mushy and gooey inside, thinking they might have one of the coolest jobs on earth. Then I get to a film like this and feel sorry for the poor crew that had to deal with it, working their hardest to do their best and all the time wondering why, oh why, this film.