I have always had sour feelings in regard to Breillat, but I should have known better than to simply write her off. I should know better than to write any director off. It is an immature way to deal with art we don't understand. I still don't get the films I've seen in the past, which is only three or four, and at least one that I couldn't make all the way to the end (Anatomy of Hell, which is insufferable).

Over the years I've read great-thinking critics who have conviction in her power as a feminist filmmaker. I guess I thought I was going to learn something about feminism in seeing her films. Years ago I went to a Chicago Fat Girl screening, partially out of curiosity and partially wanting to find out what this feminist had to say. I still think it's just a film, there's nothing more to it than that.

Later I sat for half an hour with Anatomy of Hell until I realized that I could get more out of the videos in secluded rooms in the back of rental stores -- the kind that only appeal to prurient interests. I had much the same reaction to Romance.

I came to the conclusion that however that word "feminism" is being applied to Breillat, it is most certainly a wrong understanding of the word, that she is a peddler of a kind of film that corrupts, where the audience itself becomes the pornography for her. I felt for her works, like the Supreme Court once noted: "Taken as a whole, lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value." I also said she represents a "feminist reverse-pornography" by exploiting the male's movie-going process and not allowing one to use her material as a masturbatory aid while sitting in a mainstream theater. That might be an extreme understanding, and a wrong one, but the point I was getting to is that she's a boundary pusher. The question is, "Does boundary pushing in and of itself legitimize what she is doing?" The boundaries have been pushed in better ways before. And honestly, with the availability of porn, why the need to push boundaries at all?

So when I heard about Bluebeard, I had a very loud laugh. The woman who has consistently shoved the vagina in our face for years is now directing a children's story? And perhaps even a trilogy of children's stories (Her next film is said to be Sleeping Beauty).

I decided to check it out when the DVD became available, based on a few of the friends at A&F and a review I read in Film Comment, which spoke of the work as mesmerizing. Which it is. And it is easily her best film to date.

Breillat finally comes through with a classic film, one that avoids all the manipulation and stimulation gimmickery she's relied upon in the past. In its place, she finds four girls, two of them little girls who are absolutely adorable, and relays a story that's still quite rife with feminist readings, I'm sure, but her approach is more tolerable (and even fun, in a creepy kind of way). It's like she has actually taken an interest in her audience. Her form is up to its usual high standards, and she finally weighs in with a lovely (again read: creepy) little story, which, knowing Breillat's history makes this whole event perplexing. It makes you wonder: Will the real Catherine Breillat please stand up?

I'll be looking forward to Sleeping Beauty, wondering what's gotten into Breillat. I'm still stumbling over this woman's films, but Bluebeard is a keeper, one I wouldn't be ashamed to add to my DVD collection.

There is an excellent spoiler-filled analysis of the film Here. Meantime, I'll be keeping an eye on Breillat.

Saturday, July 31, 2010

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Non-lollipop Docs.

Beetle Queen Conquers Tokyo. (2010) Jessica Oreck

The first great art-film of the year comes disguised as a documentary. Japan's insect-reverent culture is the topic at hand.

I told a friend I was going to see a film about the Japanese and their love of bugs, and he said, "Oh."I am telling you, this is a killer documentary. I believe the word I used right after the screening was, "Sensuous."

Completely uninhibited and willing to take risks, by all practical accounts the film shouldn't work. The fact that it does is a testament to the filmmakers' obvious love of the form and a willingness in general to be completely sold out to the topic. We not only get to study the fascinating bugs of Japan, which are larger and more beautiful than any bug I've ever seen, but we study the people, too, and their fascination with the little critters. They marvel at these insects for their vitality, for the sounds they make, and for the way they teach in nature.

The fascination is rooted in the 6th century in early Shinto and now Buddhist philosophy. These beautiful beetles, fireflies and crickets are a part of animist nature. According to Japanese beliefs, where the natural and the spiritual are more closely related, the universe is alive and breathing, and willing to teach -- as long as we're willing to listen. They give us insight even into ourselves.

A soft-sounding feminine narrator explains how the firefly is the signature of burning love; how the dragonfly is a symbol of warrior power; how the sound of crickets is the song of night life; how a rhinoceros beetle resembles lightning from the horns on his head, he's a guardian of power or prestige.

But if it's about honor for the insects, it's also about honor for the creation of film. The whole movie is like a love story created for the eyes -- my heart was pounding with every frame. There are images here that are soaked in miniscule beauty -- like haiku, the small poetry that was invented for the insect microverse. But then we're taken out of the insect world on a journey that shows the Tokyo crowds, Japanese children at play, the history and tradition of the religion, and the ebb and flow of their cities -- the pulse and grind of daily life. We see what the people in the streets of Tokyo might look like from a dragonfly's point of view, and then we're back on a leaf, or in a spotlight, or in a pet Beetle's cage, back with that wonderful feminine voice that narrates more philosophical musings.

It is a poetic film that keeps our eyes fixed on the screen in excitement over nature. I almost lept to my feet in applause several times only a few minutes in.

80s retro synth-pop pokes in at various points, the electro-bop heightening the fun of the experience. It drifts between this and Thom Yorke-type electronica. The two styles blend in and out of each other, giving breaks between narration which make you light up like a firefly at the wondrous sound and imagery.

Restrepo. (2010) Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger

Restrepo, named for a fallen comrade, follows a year in the life of US soldiers in the deadliest valley in Afghanistan. The Korengal Valley has actually been called one of the deadliest places in the world; Vanity Fair contributing editor Sebastian Junger and photographer Tim Hetherington spent a year there being shot at and tracking soldiers, trying to understand this war. The intense footage of our men in the region, of which photos are posted here, is more damning than even the 91,000 documents leaked about the war this week. Visuals in general are more gripping and harder to push away than the printed words in classified papers.

This 2010 Sundance Documentary Winner reports in 93 minutes why the cries "unwinnable" indeed have merit. We see decent, good, scared young men, bleeding and fighting for what their country has told them is right. The country has since abandoned the region, pulling out after scrambling men there for years and leaving assorted dead Americans in its wake. We might at some point be inclined to ask, "What for?"

The valley is a symbol for a war that cannot be won. A war that only makes matters worse for future generations. The doc is a testament to the power of truth in image. I only hope that more people choose to see it, and that it burns in them what it cemented in me.

The valley is a symbol for a war that cannot be won. A war that only makes matters worse for future generations. The doc is a testament to the power of truth in image. I only hope that more people choose to see it, and that it burns in them what it cemented in me.

My friend Darrel took part in a roundtable discussion with the directors. There is excellent info there on the valley, the war and the film. Check out the film and interview, and protest in whatever way you can.

The Most Dangerous Man in America:

Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers. (2010)

Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers. (2010)

Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith

Equal parts historical documentary, love story, government conspiracy thriller, and biography -- with keen, compelling insight for a locked-in president with a stronghold on a going-nowhere war -- the Oscar nominated doc reveals an American hero who practically leaked an administration out of office and took the Viet Nam conflict by the balls. It makes you more excited than ever for places like Wikileaks.

Dan Ellsberg was an MIT professor with a Ph.D. in Economics from Harvard, also ex-military, working the "inside" during the early days of Viet Nam reporting directly to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. The reports he made, combined with a split from his anti-war wife Patricia, brought great disillusionment to Ellsberg, who eventually photo-copied the 7,000 page report titled, "United States-Viet Nam Relations, 1945-1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense," later known as the "Pentagon Papers," which were leaked to the New York Times and almost twenty other papers, damning four administrations leading up to Nixon and promting the president himself to job out "plumbers," the thieves responsible for Watergate and breaking into Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office.

Ellsberg and his wife were (and are) incredibly media-saavy. Their interviews now are as rewarding as their courage on news shows from the early seventies. The couple form the two sides of the story; though they're interviewed separately and they tell it their own way, the story is unified when relayed and edited together.

The Nixon tapes are heavily incorporated in the story as well, showing a war-mongering man who brought us within a finger's touch of nuclear annihaltion. This was a scary, scary man in scary, scary times. He sounds as horrible as any criminal dictator you've ever read about in a trial. He sounds evil, and narcissistic, too -- a combination that can blow up a planet.

The doc is highly recommended for those of us old enough to remember events surrounding Nixon from when we were children, but young enough to not be aware of the details -- probably most of us under 40.

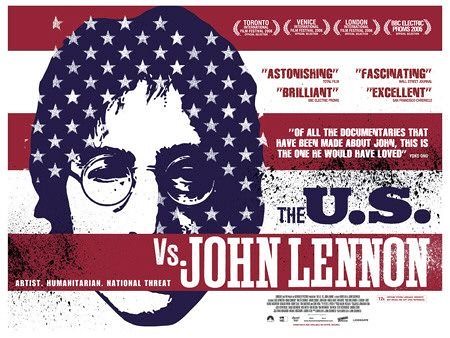

The U.S. vs. John Lennon. (2006) David Leaf and John Scheinfeld

Functioning as the perfect second film in double-feature with The Most Dangerous Man in America, the doc zeroes in on the

rocker-cum-protester, who was also considered dangerous by the Nixon administration. He was even put on trial with young wife Ono in an effort to be deported for treason. I've never really been all that much of a Beatles fan (I thought if you're a Doors fan you're not supposed to be), but the doc made me see John Lennon as more than a hippie, more than a talented musician, even more than an artist -- he was also an outspoken political activist and a defender of human rights. And he used his talents to showcase his thoughts. In particular, some of the performance art with Ono was simply genius. He knew he would get noticed, he knew something had to be said, he did it and went to trial because of it.

It's an inspirational film that makes you want to stand up for what's right -- and listen to more of Lennon's music in the process.

The Atom Smashers. (2009) Clayton Brown and Monica Ross

The mystery behind the veil plays out in The Atom Smashers, which never received theatrical release. One of the better aspects of modern viewing is that good material will find its way to DVD whether created for theatrical run or released via television. This little doc, a PBS special, is available either through iTunes or Netflix, and it is well worth a look.

I have to admit I have a vested interest -- I grew up less than twenty miles from Fermilab, the mysterious atom smashing facility that it covers. People in the western suburbs of Chicago tend to think of this place as a little creepy. I've heard there have even been protests from those who think Fermilab is going to blow up the world (probably aging hippies who have run out of drugs).

I've been there once. I have a friend who works there in IT. I've asked him about the doc, but he didn't have much to say. He works there every day, perhaps it's too much to see the film as well.

Particle physicists at Fermilab operate and observe the collision of particles in a four mile-long particle accelerator (a very, very large and expensive microscope) called the Tevatron. The doc pits them racing against the LHC, a 15 mile-long accelerator being built in Switzerland, for the discovery of the theorized Higgs boson -- a particle which would actually explain matter. So we are looking at the microverse to figure out the universe, a similar idea to Beetle Queen Conquers Tokyo. But of course in that film we are dealing more in the realm of philosophy and man-and-insect relations. Here we are dealing with cold, hard facts. The scientific standard is empirical evidence.

But the goal in approach is somewhat the same. Here, it's a search in math analysis to understand the natural world. It's a fascinating concept which brings life to regular science, and the scientists are nearly religious in their passionate search to prove the theory.

It is an important documentary for its reminder of America's original strength found in scientific research, and how research is now politicized, cut back and underfunded (so we can continue an unjustified war). The U.S. was a world leader from the sputnik-era on, advancing science from the microscope to the military, from the bottom of the ocean to NASA. The idea of science still making an important contribution, a difference in the world, is now eroding in the face of recession and the fiscal budget.

But when politics funds your experiment, you've got to nod and hope for the funds to keep flowing. At the end of The Atom Smashers, the Higgs boson still hasn't been found. And Switzerland is now fully functional and in the race to be the first to find it. The funding goes up and down, back and forth. It gets taken away and handed back again. The politicians can't decide whether this is still important after twenty years of research.

You may not have thought of science as being "fun" in a while. The Atom Smashers takes a look at the daily lives of ordinary scientists, and for all their intelligence and over-scrutinized theories, there's a passion for their work that's great to watch. Definitely worth a look.

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

I Am Love. (2010) Luca Guadagnino

I Am Love left me stunned and glued to the screen. From its opening, over-sized and larger than life title sequences, reminiscent of classic monochrome Italian film, to its final, pulsating, fanfare conclusion --

it is so deeply thought through, so well thought out!, but never to the point of over-intellectualizing. Superb, raw acting punctuates the deep thinking going on, bringing warmth to the thinking process like a beating heart to the brain. This is one of those rare moments in cinema where all the parts and people flow seamlessly together, a unified whole creating a stylish work of art that is suited for the big screen.

And check out the color scheme in the poster above. You can read so much into it, it is the perfect introduction to the film.

Tilda Swinton plays Russain immigrant Emma now living in Italy with the rich Recchi family, in a mansion all their own, somewhat trapped by their wealth. The family keeps her at a friendly distance; her husband treats her like a propped-up trophy. As long as she doesn't ruffle any feathers, she will always be provided for. She won't lack a material possession.

She's as aloof in the family as she is from her Russian roots. At one point she admits she can't remember her Russian name.

When her son introduces her to Antonio the chef, a much younger man who shares her passion for a delectable dish, the attraction is immediate and fierce. She represses it at first -- she knows these thoughts lead nowhere good. In an opportunity to cook for her, his meal of prawns breaks through before he can, and suddenly she's willing to risk the mansion, the trips, the cars, the clothes. She'll risk everything to chase after that thing that eludes her: passion.

Two tragedies directly result from this risky chase. The first, an accident she never would have dreamed, a thing so horrible that it throws her completely off, into mourning and grieving beyond help. The first tragedy prompts her to spur a second tragedy to birth. In the film's final, devastating scene we can't be certain how her choice will affect her -- or for that matter, how it will affect her husband, her lover, her grown-up children. But I Am Love is less about narrative or choices or consequences, and more about expression -- perhaps expressionism -- in the here and now of the Recchi clan.

Consider a scene in the middle with Emma and Antonio making love. Close, tight shots of entwined skin in sunlight exaggerate connectedness and not necessarily sexuality, connecting two lost souls that have strayed together. While at many points I Am Love seems to borrow from Hitchcock and Vertigo, the sex more resonates with a recent Claire Denis film, Vendredi soir. The way Denis captured that Friday Night tryst is visually and thematically similar to Guadagnino's motion capture of Emma and Antonio outdoors: the two, now one in flesh, pressed passionately against and even inside one another, and the arousal and need that connect them (though they, and we, know they cannot be together) is caught so closely, lensing from inches, skin that expresses desire over release, understanding over biological urge. Soul-gazing is how the viewer joins in with this union. It is sensual but not overtly sexual -- not objectifying or gratuitous.

The motion in that scene is important too, because Emma and the camera have already established a spatial, physical relationship that constantly reflects and reacts to her emotional state of the moment. There are many types of cinematography in I Am Love, but three caught my eye in relation to Swinton's character -- three styles that took my breath away upon initially seeing this in the theatre.

The first I will simply call as I see it. It is cubism. It is the camera bringing static shots that are always edged off in a square or rectangle. These shots are almost always used in the Recchi household. In this cold, atmosphere of somewhat distant family members, the characters are caught in a cubist landscape. Squares and rectangles from walls and doorways form angles that hold them in. A spatial distance is created that imitates the distance in the business-like clan. At the front doorstep and stairs leading up to the entrance, at the dinner table, with the wine cups and candles and dinner plates, with people divided exactly in half around a large oval table -- the edges are a boundary holding the people inside. Perhaps "held inside" like Swinton's character, feeling trapped for a number of years -- the emotional state is the visual reflection, and vice versa.

The edges form angles that stand for entrapment. The camera even lingers on several frames displaying photos of family members.

Almost immediately when Swinton/Emma is away from the stuffy clan and walking the city streets, everything goes from that cubist/entrapment/held-in approach to the second approach -- a circular, more rounded approach, which is clear of any straight edge and feels more liberated. She's free. Even the city's architecture is less restrained than the confines of the Recchi exterior. In this rounded part of the story Emma finds a CD which represents alternative living, how circular life can be outside of the edges. Emma's hair is zoomed in on in a spiral on the back of her head. These shots and props represent escapist delight, freedom from the confines of the edged Recchis.

Very soon, a third kind of cinematography emerges. It is alive, it is moving and using wonderful tracking shots to bring kinetic energy to the story. Everything in the lens follows Emma in love, sometimes whipping around in a dash. These moments of motion don't let up until the lovers finally meet, and then -- BAM! Things slow down quite a bit. We're in that moment like Vendredi soir, captured in these close, tight shots with light all over the lovers' skin. The moment slows down to a longing lull because it is the greatest "here and now" part of the story.

After the love making scenes we really begin to move into hyper speed, but something horrible needs to happen to rip all these emotions from both the character and the camera. As Emma begins to pull away, she has to go back to those cold, dead, angles that have held her in, and break free. She has to return to the house --

she has to break through some walls and windows. They are the walls and windows of herself, the house, and the relational walls and windows that she's been fading in for too long.

Moralists will hate the ending of this film. I can't say that I disagree, however, I'll always disagree with a moralist first and give art the benefit of the doubt.

This is a rare film, a film lover's delight, with wonderful acting, lensing and music that builds to a huge, emancipating, colossal climax, and what has finally happened is as honorable as it is terrifying. Swinton brings it in I Am Love. She is full-force and needs to be nominated for an Oscar, whether the film is in Italian or not.

But she doesn't bring an easy answer when everything is said and done. It's like hard times in real life, but rendered in such a lovely, touching way.

it is so deeply thought through, so well thought out!, but never to the point of over-intellectualizing. Superb, raw acting punctuates the deep thinking going on, bringing warmth to the thinking process like a beating heart to the brain. This is one of those rare moments in cinema where all the parts and people flow seamlessly together, a unified whole creating a stylish work of art that is suited for the big screen.

And check out the color scheme in the poster above. You can read so much into it, it is the perfect introduction to the film.

Tilda Swinton plays Russain immigrant Emma now living in Italy with the rich Recchi family, in a mansion all their own, somewhat trapped by their wealth. The family keeps her at a friendly distance; her husband treats her like a propped-up trophy. As long as she doesn't ruffle any feathers, she will always be provided for. She won't lack a material possession.

She's as aloof in the family as she is from her Russian roots. At one point she admits she can't remember her Russian name.

When her son introduces her to Antonio the chef, a much younger man who shares her passion for a delectable dish, the attraction is immediate and fierce. She represses it at first -- she knows these thoughts lead nowhere good. In an opportunity to cook for her, his meal of prawns breaks through before he can, and suddenly she's willing to risk the mansion, the trips, the cars, the clothes. She'll risk everything to chase after that thing that eludes her: passion.

Two tragedies directly result from this risky chase. The first, an accident she never would have dreamed, a thing so horrible that it throws her completely off, into mourning and grieving beyond help. The first tragedy prompts her to spur a second tragedy to birth. In the film's final, devastating scene we can't be certain how her choice will affect her -- or for that matter, how it will affect her husband, her lover, her grown-up children. But I Am Love is less about narrative or choices or consequences, and more about expression -- perhaps expressionism -- in the here and now of the Recchi clan.

Consider a scene in the middle with Emma and Antonio making love. Close, tight shots of entwined skin in sunlight exaggerate connectedness and not necessarily sexuality, connecting two lost souls that have strayed together. While at many points I Am Love seems to borrow from Hitchcock and Vertigo, the sex more resonates with a recent Claire Denis film, Vendredi soir. The way Denis captured that Friday Night tryst is visually and thematically similar to Guadagnino's motion capture of Emma and Antonio outdoors: the two, now one in flesh, pressed passionately against and even inside one another, and the arousal and need that connect them (though they, and we, know they cannot be together) is caught so closely, lensing from inches, skin that expresses desire over release, understanding over biological urge. Soul-gazing is how the viewer joins in with this union. It is sensual but not overtly sexual -- not objectifying or gratuitous.

The motion in that scene is important too, because Emma and the camera have already established a spatial, physical relationship that constantly reflects and reacts to her emotional state of the moment. There are many types of cinematography in I Am Love, but three caught my eye in relation to Swinton's character -- three styles that took my breath away upon initially seeing this in the theatre.

The first I will simply call as I see it. It is cubism. It is the camera bringing static shots that are always edged off in a square or rectangle. These shots are almost always used in the Recchi household. In this cold, atmosphere of somewhat distant family members, the characters are caught in a cubist landscape. Squares and rectangles from walls and doorways form angles that hold them in. A spatial distance is created that imitates the distance in the business-like clan. At the front doorstep and stairs leading up to the entrance, at the dinner table, with the wine cups and candles and dinner plates, with people divided exactly in half around a large oval table -- the edges are a boundary holding the people inside. Perhaps "held inside" like Swinton's character, feeling trapped for a number of years -- the emotional state is the visual reflection, and vice versa.

The edges form angles that stand for entrapment. The camera even lingers on several frames displaying photos of family members.

Almost immediately when Swinton/Emma is away from the stuffy clan and walking the city streets, everything goes from that cubist/entrapment/held-in approach to the second approach -- a circular, more rounded approach, which is clear of any straight edge and feels more liberated. She's free. Even the city's architecture is less restrained than the confines of the Recchi exterior. In this rounded part of the story Emma finds a CD which represents alternative living, how circular life can be outside of the edges. Emma's hair is zoomed in on in a spiral on the back of her head. These shots and props represent escapist delight, freedom from the confines of the edged Recchis.

Very soon, a third kind of cinematography emerges. It is alive, it is moving and using wonderful tracking shots to bring kinetic energy to the story. Everything in the lens follows Emma in love, sometimes whipping around in a dash. These moments of motion don't let up until the lovers finally meet, and then -- BAM! Things slow down quite a bit. We're in that moment like Vendredi soir, captured in these close, tight shots with light all over the lovers' skin. The moment slows down to a longing lull because it is the greatest "here and now" part of the story.

After the love making scenes we really begin to move into hyper speed, but something horrible needs to happen to rip all these emotions from both the character and the camera. As Emma begins to pull away, she has to go back to those cold, dead, angles that have held her in, and break free. She has to return to the house --

she has to break through some walls and windows. They are the walls and windows of herself, the house, and the relational walls and windows that she's been fading in for too long.

Moralists will hate the ending of this film. I can't say that I disagree, however, I'll always disagree with a moralist first and give art the benefit of the doubt.

This is a rare film, a film lover's delight, with wonderful acting, lensing and music that builds to a huge, emancipating, colossal climax, and what has finally happened is as honorable as it is terrifying. Swinton brings it in I Am Love. She is full-force and needs to be nominated for an Oscar, whether the film is in Italian or not.

But she doesn't bring an easy answer when everything is said and done. It's like hard times in real life, but rendered in such a lovely, touching way.

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Come and See. (1985) Elem Klimov

On that site, Come and See was one of the easiest five-star ratings I've given. The film masterfully accomplishes what it sets out to do. There isn't a false note in it. But that doesn't make it an easy film to take in.

It's the story of Nazi infiltration of the Soviet republic of Byelorussia, and a young man Florya and how the war changes everything about him. In a devastating performance, actor Aleksey Kravchenko is transformed even physically from a boy longing to join the defense in pursuit of war's glory, to a completely annihilated shell of a soldier -- beaten, wrecked, mentally disfigured.

There are war films that seem to glorify the battle action, showing every bullet and every point of entry -- but some are as honest as they are distressing, and they can only be classified as anti-war. Come and See is such a film, classified on Florya's face as easily as it is classified in the harrowing, blood saturated script.

In terms of film comparison I thought of the personification of the landscape and the brute poetry of The Thin Red Line. In bizarre, trippy moments I remembered the surfing-under-attack and drug-induced-bridge sequences of Apocalypse Now. I haven't seen

Stalker -- I'm hoping to change that soon -- but I was also reminded of Tarkovsky's The Sacrifice, which was released only a year after Come and See. It's as fierce as Platoon, but as fiercely Russian as any Russian film I've encountered.

Adrian Danks at senses of cinema has some incredible insight to Come and See. I can't add much to his outstanding writing, but let me stress for a moment the wonder of the film's sound.

Florya is accused at various points of dealing with the onset of deafness, which could actually be attributed to an early scene in which he dodges falling bombs. Sonic shifts give us insight to how he hears -- from muted panning screams to the impact of an explosion that's scorched and muffled, and more quiet than it should be. Panic becomes another character in the film, and sound is its contribution to the dialogue. Marching armies, stampeding citizens, the enemy's triumph -- it all plays a crucial part. How Florya hears widens his perception of the story's trauma. The hyper-expressive sound in Come and See is riveting, terrifying to take in, and when heard through the ears of one entrenched in the insane, it brings a forcefulness that astounds and sometimes overwhelms the senses.

If I ever have the opportunity to see it in a good theatre with bellowing speakers, I won't hesitate to change my plans for this crunching mind-melter of a film.

Monday, July 19, 2010

Jacques Audiard Then and Now.

A Prophet. (2010)

Read My Lips. (2001)

The film has critics and cinephiles going nuts, and honestly, I can't blame them. It is an incredibly well-acted gangster-style film filled with the boiling tension this genre best manifests. But it is nowhere near Audiard's best film. In fact, on a scale of "masterpiece" to "well-made film," Audiard has been working backwards over the course of the last decade. His three films in the past ten years have each tied together criminals and gangsters -- it's the stuff he likes to deal with -- but the first time he spun it still remains his best, a picture with sizzling chemistry between male and female leads and magnetic visual flourishes to delight a paying crowd.

I had the unique opportunity to catch Read My Lips on the big screen only moments after A Prophet. The former filmically levels the latter.

It's the story of Carla (Emmanuelle Devos, who I also adore in

La Moustache), a partially deaf secretary who works with hearing aids, and Paul (blue-eyed Parisian ladykiller Vincent Cassel), a bad-boy ex-con love interest. They meet when Carla's boss decides her work load is too heavy and she needs to find an assistant. Paul is completely unqualified for office work -- he can't type or take dictation and he can't even figure a fax machine -- but he applies anyway, and Carla reluctantly hires him when she learns he's just out of prison. She's intimidated and fascinated with him, and she's been looking for a man in the position anyway. In a humorous scene where she dictates the job offer, it's obvious she's looking for more than just a work-mate.

Carla spends her lunches alone perusing fashion magazines, but reads coworkers' lips at other lunch tables. She knows when she's the subject of gossip. Her secret about reading lips is revealed to Paul when he begins to share his lunch time with her.

Paul has had those bad-boy moments in life, you can taste his past in his general demeanor, but he isn't necessarily the bad guy in the story between the two. In fact, he may have had a fresh start coming out of jail if it weren't for Carla prompting him to steal an office document for her advantage. He doesn't want to -- he says it could get him in a lot of trouble. She reminds him that he owes her. She not only got him the job, but an advance on his pay, and a place to live.

A tricky relationship forms over who owes who more. Paul uses Carla's ability of reading lips to work to his advantage. He wants to pull off a heist from some shady characters to whom he owes a large amount of money, and her ability comes in handy at springing their secrets. The two begin to tumble down a hole of who owes how much to whom, which obligation is bigger, how far down the hole each is willing to fall, and how they are going to correct all the mishaps and mistakes made along the way.

An attraction is formed, but as they each pile up the obligations, the attraction is put on hold in favor of the next business tryst. The attraction keeps us interested in the story, frustrated as things get when we watch the characters interact. So many times they are simply put off by the obligations. When one walks away from the other, they'll whisper, "Bastard!" or "Bitch!"

It's a well rounded film that ends on exactly the right note. It is believable, interesting, even fun to watch as it develops. It's another good Euro-thriller to throw in your queue, but it was better on the big screen. By far.

Believable, and, to a point even interesting, A Prophet has an IMDB summary which reads, "A young Arab man is sent to a French prison where he becomes a mafia kingpin." After seeing the film nothing changes about that description at all. The pre-viewing teaser and the post-watching summary are the same. We've watched a seemingly good bad-guy turn into a very bad bad-guy over a long 155 minutes of viewing time. I can't quite get the point beyond that, but there's been some good reflection on the film from other sources.

Critic James Bowman has said:

When the movies abandoned the moral context in which they once represented crime and criminals — even when the morality was inverted for political reasons and the bad guys became good guys and the good guys bad — they found that they had nothing to put in its place but a kind of voyeurism.This may have something to do with my reaction, which isn't necessarily negative as much as it is ambivalent. I can see why people are raving. It's well made. But the characters aren't. They're just thrown into a prison and left to fend for themselves. We only know as much about them as other prisoners do, which creates realism in the way they relate to each other, but is utterly boring because we don't have a background by which to judge them.

I lost interest after about half an hour. I disengaged from the story and turned into one of those voyeurs.

The thing Audiard does in Read My Lips that he shies away from in

A Prophet, understandably so, is simply have a bit of fun. Similar iris shots in both films form circular masks used to great effect around the characters, but it is much more scrumptious and fun and used with greater repetition in Read My Lips.

A Prophet can't have fun because there's no fun in the script to be had. When there's no fun to be had by any of the script, acting, or rendering, there's no fun to be had by the audience either.

Both of the films, and in fact Audiard's 2005 The Beat That My Heart Skipped qualify as "good" films. In the case of the two I'm comparing, one is simply easier to take, and you actually desire a repeated viewing. I can't imagine trying to sit through the lengthy A Prophet again just to see if I got it wrong the first time. And I can't believe how much talk it's getting this year without looking at Audiard's stronger, more unnoticed works works of the past.

Saturday, July 17, 2010

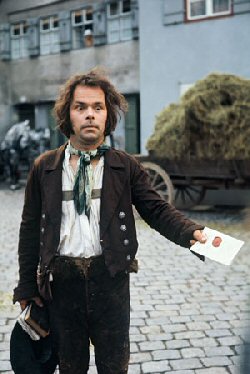

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. (1974)

Werner Herzog

I recently went back to watch Germany's most famous "non-actor" Bruno S. in an earlier performance than the one I wrote about in Stroszek. Chronologically speaking, I watched the two backwards in time, but I'm glad I saw them in the order I did. The Enigma of Kasper Hauser is the role Bruno S. was destined to play, but Stroszek is a film Herzog was destined to direct. (One of many!) Seeing Stoszek first is a better way to work into this classic Herzog double-feature; it is also a more natural build to the climax of the enigmatic Hauser character.

Hauser's story is very simply told, and according to German history, true. As a young man or perhaps a teenager, he was discovered standing freeze-frame in the town square in Nuremberg, 1828, a note in one hand and a hymn book in the other. He could barely walk, he couldn't speak, reason, eat, sit, anything -- he knew nothing, understood nothing, had been nowhere, had seen no one. The townspeople took him in, first the jailer and then others and he learned the language from children. As time went on he learned how to properly sit, properly eat, and properly function in a social setting. He got to the place where he could string words and then sentences together. A few years later he penned his story as he understood it.

The story he tells is something like this: from before he could remember, from the time he was a baby, he was held in a dungeon twenty-four hours a day -- no bath, no mirror, no contact with anyone, ever. A bowl of food was pushed in every day. He never knew to speak or spell because no one was there to teach him; he couldn't sit, stand or walk because he was chained in a crouching position. Grunting and playing with a small toy horse, he was kept there for years, a prisoner of no wrongdoing.

Looking back now you can understand Herzog's interest in the story at the beginning of his career: Hauser is a perplexing character whose origins remain a debated mystery -- Herzog, one of the more quizzical directors in history, has taken such license in telling his own story that we don't know what to believe about his origins, either. It is sheer enjoyment and just plain fun to go back and see Herzog's interest in enigmas even this early in his career.

Hauser was stabbed to death a few years after he began to speak. Such an action made his existence the stuff of conspiracy theories and German controversy. It is said that he came from royal blood, a bastard child that wouldn't be let near the throne. Others claimed he was a bum, a fraud with a novel idea and a way to be taken care of.

The film's original title is Every Man For Himself and God Against All. There is a point in Hauser's story when he asks why everything is so hard for him, a question even people raised in "normal" circumstances ponder. He is reminded of the progress he's made to that point and the people that want to help him succeed. "The people are like wolves to me!" he replies.

There is a naturally occurring phenomenon in the heart of man, that when he is beaten down by those he believes should stand tall and be better than they are, he'll perceive God in much the same light. The obstacle of the God relationship is like the sun eclipsed by wrongdoing. Kaspar Hauser had it worse than any of the rest, but in him our struggles are reflected.

Hauser's story is very simply told, and according to German history, true. As a young man or perhaps a teenager, he was discovered standing freeze-frame in the town square in Nuremberg, 1828, a note in one hand and a hymn book in the other. He could barely walk, he couldn't speak, reason, eat, sit, anything -- he knew nothing, understood nothing, had been nowhere, had seen no one. The townspeople took him in, first the jailer and then others and he learned the language from children. As time went on he learned how to properly sit, properly eat, and properly function in a social setting. He got to the place where he could string words and then sentences together. A few years later he penned his story as he understood it.

The story he tells is something like this: from before he could remember, from the time he was a baby, he was held in a dungeon twenty-four hours a day -- no bath, no mirror, no contact with anyone, ever. A bowl of food was pushed in every day. He never knew to speak or spell because no one was there to teach him; he couldn't sit, stand or walk because he was chained in a crouching position. Grunting and playing with a small toy horse, he was kept there for years, a prisoner of no wrongdoing.

Looking back now you can understand Herzog's interest in the story at the beginning of his career: Hauser is a perplexing character whose origins remain a debated mystery -- Herzog, one of the more quizzical directors in history, has taken such license in telling his own story that we don't know what to believe about his origins, either. It is sheer enjoyment and just plain fun to go back and see Herzog's interest in enigmas even this early in his career.

Hauser was stabbed to death a few years after he began to speak. Such an action made his existence the stuff of conspiracy theories and German controversy. It is said that he came from royal blood, a bastard child that wouldn't be let near the throne. Others claimed he was a bum, a fraud with a novel idea and a way to be taken care of.

The film's original title is Every Man For Himself and God Against All. There is a point in Hauser's story when he asks why everything is so hard for him, a question even people raised in "normal" circumstances ponder. He is reminded of the progress he's made to that point and the people that want to help him succeed. "The people are like wolves to me!" he replies.

There is a naturally occurring phenomenon in the heart of man, that when he is beaten down by those he believes should stand tall and be better than they are, he'll perceive God in much the same light. The obstacle of the God relationship is like the sun eclipsed by wrongdoing. Kaspar Hauser had it worse than any of the rest, but in him our struggles are reflected.

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

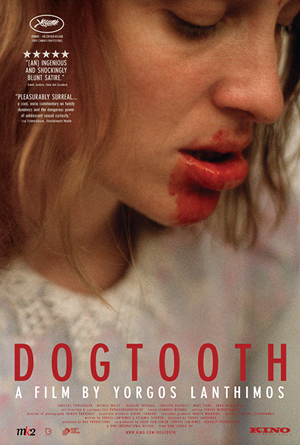

Dogtooth. (2010) Giorgos Lanthimos

But while Dogtooth contains that same edge of grittiness and mixed surrealism throughout, it cannot simply be swept away, dismissed as unbridled decadence. The coming of age story from Greece is the most bizarre and disturbing film on screens so far this year, focusing all its strength on an isolated family, a wife and children literally held captive by an authoritarian husband/father. But an outright dismissal, even in the wake of scenes that left me wishing I weren't included in the viewing process, would be a reading void of interpretations regarding governing lies and communal order, whether in family mode or nationalistic oppression, and the misinformation in those atmospheres put in place to hold rule intact.

This probing of a family lied to and stashed away in a "bunker" reminded me of no particular film I've seen but brought to mind lyrics of one of my favorite Arcade Fire songs: "We know it's just a lie / Scare your son, scare your daughters / Every time you close your eyes -- Lies! Lies!"

At the heart of the story is an eccentric, reclusive family of five -- or six, and maybe soon to be eight or nine, depending on how you interpret some of mom and dad's lies -- wherein the visible children, two daughters in their mid-teens and a son around the same age, live in an industrialist's large house, deceived about the outside world and unable to make contact with it. A large wall is built around the home. The children aren't allowed to cross over and have never been on the other side, where they've been told a supposed 'nother brother might live. They toss things to him to see if he'll react. They gaze at the fence in fascinated wonder, unsatisfied with the large house and outdoor swimming pool in the home they've always known.

Dad is the great deceiver. He's the only one with the key and the car to get outside the family property. He brings home a woman from work to take care of the sexual needs of his son. He teaches the children wrong words for items he doesn't want them to understand. He plants large fish in the swimming pool to plant the notion that dangerous outsiders can appear at any time. When the fish are finally noticed by one of his daughters he descends into the pool with a spear.

Dad has no background which defines him, no dialogue which explains his need for control. Perhaps he is better left not understood, only known as a sore source of power, a character who will bowl you over, whether through psychological means -- the withholding of information, the enforcing of his will -- and even physical assaults, attacks which finally give us a visual of his rotten core.

Mom stays home with the kids, also obedient to dad and his ways. We're never quite sure whether they're creating this world together, whether she's fully vested in the home's drama or whether she's held like a slave, like a 50s businessman's trophy wife, lapping at the heels of her husband. Other than dad she is the closest to the outside world -- she hides a telephone in her bedroom so she can call him at work when she needs.

A kitten wanders onto the property while Dad is gone to work. As the daughters cling to each other inside, staring out the living room window, screaming in blinding fear, son takes a large axe and chops the cat to a bloody screaming death in the front yard. Dad later warns about these dangerous cats -- they are preying monsters to be feared. He teaches mom and the children to get on all fours and bark like dogs to protect the property.

One of the reason the Arcade Fire song is so fitting are the themes of lying to your offspring about the nature of human sexuality. Dogtooth in places, ever so severely deals with the ramifications of hiding truth from innocent eyes, as maturing kids now begin to awaken. With no one to provide direction and with no nourishing guidance from their parents, what more would we expect of the kids than to completely misunderstand their sexual identities and become thoroughly screwed up?

When the outsider, the workmate originally brought home to satisfy the son, becomes more of a burden than an answer, introducing foreign concepts in a home that won't allow it, the relationships that were once just typical of sibling rivalry -- playing games to see who could hold their breath the longest, who could find mom first with a blindfold, who could take on the greater pain or wake up first from passing out -- become immoral without even the knowledge of the fruit they bit into. It's the innocence of the Garden without the Knowledge of the Tree. They become sad in their daily dealings; adult depression drifts into minds held captive in first grade.

Dogtooth has a linear-driven, naturalist style that occasionally plummets surrealist, almost Lynchian horror and avant-garde boundary pushing of social order and acceptance. Incestuous scenes are an affront to any intelligent watcher, and yet here, in this family, with these misplaced taboos and outlandish domestic priorities, you've got to think that the wrong that happens is exactly how it would naturally play out. This in turn is a statement about whatever anti-authoritarian stance you wish to read into, interpret or suggest.

The director is on record for letting the film speak for itself. He is open to the interpretation of the viewer. For this viewer it is both sickening and illustrative. It's a film I can't recommend for anyone but contains certain ideals I wish to recommend for all. It suggests a harder life when idly buying into the lies of those who have walked in front of you. It wants you to question your authority figure, and suggests there are consequences when you don't. It is the reality of existence when held at a distance from mom and dad's unspoken private lives.

Saturday, July 10, 2010

The Girl Who Played With Fire. (2010)

Daniel Alfredson

I was overly excited going into the second film in The Millennium Trilogy, having now seen the first film twice and knowing how much I've come to admire it. This was easily my most anticipated movie event of the summer.

Most of the time in my trips to the theater I'm wanting to learn, to stretch, to see the world, to find new and fresh perspectives. I don't get particularly excited to see most movies, but I enjoy the chance to go and am typically rewarded with insight into other cultures, or the human condition, or thoughts about God, existence in general.

There are other times when I become an all-out nerd, practically shaking in anticipation, with almost a sweat on my brow during the opening trailers, telling all within earshot how lecherous I am, how I've been waiting and waiting to see this! I'm like a three year-old boy with a brand new Tonka Truck, who, you'd better watch out because I might wet my pants at any moment.

Such was the case with this film.

Yes, I really am that much a film nerd.

But I didn't leave the theater any place close to feeling the same. I didn't have that high that you get after sitting through something amazing. Instead I left bewildered, confused, exasperated and disappointed. I read interviews and all the love-ins for the new installment. I got more frustrated thinking I'd missed it. I may have, but I've got a few points to offer.

The Girl Who Played With Fire is a good thriller, and it is fun to see these cool Swedes in action yet again. But the plot, which seems simple in retrospect, carries with it loose ends that I can't quite tie together, and it is a far cry inferior to The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.

To at least partially understand why it doesn't stand up you've got to first understand all the different names involved here that weren't present in the original film. I'm not talking about the cast. Our cast is the same, with Noomi Rapace playing Lisbeth Salander, the gothic enigma darkchick whose back has a scary-giant dragon tattoo, and Michael Nyqvist as Mikael Blomkvist, the investigative journalist most likely in love with darkchick but he's fresh out of jail wondering where she ended up.

But Daniel Alfredson takes the director's chair from Niels Arden Oplev. Nikolaj Arcel and Rasmus Heisterberg turn over their screenwriting credits to Jonas Frykberg. And Peter Mokrosinski takes over the cinematography from Jens Fischer and Eric Kress. It's an entirely different team replacing the one that brought the success of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. It's not something I thought about going in, but it makes a whole lot of sense in hindsight.

Salander, who solved two conspiracies in the first film, is at the heart of a new conspiracy here. The guardian she took vengeance against for rape is murdered, and matching fingerprints on the gun and a found video of the rape have police wanting her in for questioning. If you saw the first film, you know that Salander doesn't like the police very much. In fact, she wants nothing at all to do with them. Ever. And being innocent, she goes on the lam, using all her expertise in security and hacking to collect pieces to prove her innocence.

Blomkvist, now un-disgraced and working once again at Millennium magazine, helps Salander as best he can. They leave messages for each other in cyberspace. They hunt clues on their own and report when they find something interesting. They never meet in person, in fact the story picks up a year after the original and instead of meeting they take on other lovers. But they keep tabs on each other while apart.

I don't think I wanted a story where the two wouldn't meet up again. The kiss at the end of the first film didn't feel like it was leading nowhere. That they held hands during one of their last moments in bed, a sign of closeness that wasn't expected, and that Salander finally visited her mom in the nursing home after years of being away, and that the story wrapped up with so many nice bits of reconciliation, had me thinking Salander had softened, that she might take a new approach -- that even against her own understanding when telling her mom, "No one should fall in love," she was perhaps finding love to be more than a feeling, but a commitment to another, even for purposes of busting out of isolation.

But isolated she remains except for tracks left on the Internet.

I don't like the setup, and that may be original writer Stieg Larsson's fault more than the team I mentioned. Still, a gratuitous sex scene that served nothing to advance the storyline (and reminded me of older days when R-rated films meant an obligatory sex scene within the first 40 minutes), and a confusing mess of a plot and a few subplots leave me thinking that the screen writing couldn't squeeze the book into the span of two hours. When the credits rolled, I thought we were half-way done. The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo is over 2-1/2 hours long. I guess I was expecting everything to be like it was there, with a wonderful ending that tied all the loose ends together. Instead, it ended, and I'm hoping that something in the third film tells us all that I missed. Otherwise, it is an undesirable film on its own.

In a way, the concluding film could actually redeem some of this, depending on whether some of what I just saw is actually explained.

But nothing will make up for one of the final scenes in particular, a riff on the second Kill Bill film, that left me stunned at its unbelievability -- so stunned that I stopped by a Borders on the way home simply to see if the same thing is in the end of the book. It is. And that is unfortunate. It is the first time I've seen actual laziness in the creative process for the fiction at the heart of these stories.

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

The Horseman. (2008) Steven Kastrissios

Not to be confused with Jonas Åkerlund's 2009 cheese offering Horseman, a Dennis Quaid film that I only remember from writing in my 2009 Film Journal. It was, "So awful I wanted to kick myself in the teeth."

Not that Kastrissios's The Horseman is all that much better.

What it lacks as a cheese plate it makes up for in muscle -- and torture, too, which everyone says is the new porn -- and loads of gore measured in tons of blood, and that same menacing myth I mentioned in my review of Harry Brown -- that a violent act can redeem a wrong.

I'm going to try to see less revenge movies, because they all seem to be saying the same thing, and so am I.

But Harry Brown is actually a good starting point for comparison. Both are revenge films. Why would I sit here like Roger Ebert (much as I love the man) and try to describe a plot in The Horseman? It's a revenge film. What more do we need to know? The only thing that saves it from being as horrible as Harry Brown is that The Horseman is at least about a dad avenging the murder of his daughter.

I've got a little girl. I can buy into that. If anyone wanted to hurt her there's little doubt I would want to hurt them back. But it wouldn't make it any more right, and if I were to put the brutality of The Horseman into practice it would rightfully land me behind bars -- something not shown in the film, and only hinted at.

Had writer/director Kastrissios actually chosen to show the killer in a cell at the end, it might have made the film easier to swallow. As it is, without a rendering of the consequences of vengeful actions, it's little better than simply enjoying, almost worshipping blood for blood's sake. So when you watch the torture scenes, you might as well get off, too. Because you've only got the joy of the image.

The thing that sticks out most is how unrealistic and vacuous the story itself is, glorifying another anti-hero as he completely goes ballistic on his enemy, and sometimes has the tables turned and becomes the victim of his torturous foe. It reminds me that it is harder to actually obey the law and trust in it for justice. Even harder is it to be the person Christ was seeking when he threw out things like, "Love your enemy."

It's easier to just lose it and uncap all that anger, to pound and slash, to attack and kill, to cover yourself in blood and drown in the entrails of your enemy. To seek redemption in torturing your enemy. Gosh, I didn't even think of the political ramifications -- but how brainless and bestial is that?

The film has bragging rights in that it was fully produced in Queensland, Australia. Most of the shoot was filmed in Brisbane. I've been to Brisbane four times, and I've met a lot of kind, good folk there. I never met anyone in Brisbane like the hopeless characters in The Horseman, but the film seems to suggest that only hopeless people live there. It would have been nice if there were even one decent figure in the film to hang your hat on. But there's not. The story gives us one young lady who acts as a stand-in for the killer's lost daughter, but she's just lost enough to make us not really care.

This is not the fault of the actress. She was fine in her performance, maybe even great. She was unfortunately trying to bring life to a one-dimensional celebration of violence. She simply couldn't save Kastrissios from himself and his own pen.

I hope in the future he considers the heart, and not just for stabbing it, either.

File under: The Myth of Redemptive Torture: A Bad Time for All.

Not that Kastrissios's The Horseman is all that much better.

What it lacks as a cheese plate it makes up for in muscle -- and torture, too, which everyone says is the new porn -- and loads of gore measured in tons of blood, and that same menacing myth I mentioned in my review of Harry Brown -- that a violent act can redeem a wrong.

I'm going to try to see less revenge movies, because they all seem to be saying the same thing, and so am I.

But Harry Brown is actually a good starting point for comparison. Both are revenge films. Why would I sit here like Roger Ebert (much as I love the man) and try to describe a plot in The Horseman? It's a revenge film. What more do we need to know? The only thing that saves it from being as horrible as Harry Brown is that The Horseman is at least about a dad avenging the murder of his daughter.

I've got a little girl. I can buy into that. If anyone wanted to hurt her there's little doubt I would want to hurt them back. But it wouldn't make it any more right, and if I were to put the brutality of The Horseman into practice it would rightfully land me behind bars -- something not shown in the film, and only hinted at.

Had writer/director Kastrissios actually chosen to show the killer in a cell at the end, it might have made the film easier to swallow. As it is, without a rendering of the consequences of vengeful actions, it's little better than simply enjoying, almost worshipping blood for blood's sake. So when you watch the torture scenes, you might as well get off, too. Because you've only got the joy of the image.

The thing that sticks out most is how unrealistic and vacuous the story itself is, glorifying another anti-hero as he completely goes ballistic on his enemy, and sometimes has the tables turned and becomes the victim of his torturous foe. It reminds me that it is harder to actually obey the law and trust in it for justice. Even harder is it to be the person Christ was seeking when he threw out things like, "Love your enemy."

It's easier to just lose it and uncap all that anger, to pound and slash, to attack and kill, to cover yourself in blood and drown in the entrails of your enemy. To seek redemption in torturing your enemy. Gosh, I didn't even think of the political ramifications -- but how brainless and bestial is that?

The film has bragging rights in that it was fully produced in Queensland, Australia. Most of the shoot was filmed in Brisbane. I've been to Brisbane four times, and I've met a lot of kind, good folk there. I never met anyone in Brisbane like the hopeless characters in The Horseman, but the film seems to suggest that only hopeless people live there. It would have been nice if there were even one decent figure in the film to hang your hat on. But there's not. The story gives us one young lady who acts as a stand-in for the killer's lost daughter, but she's just lost enough to make us not really care.

This is not the fault of the actress. She was fine in her performance, maybe even great. She was unfortunately trying to bring life to a one-dimensional celebration of violence. She simply couldn't save Kastrissios from himself and his own pen.

I hope in the future he considers the heart, and not just for stabbing it, either.

File under: The Myth of Redemptive Torture: A Bad Time for All.

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

The Secret in Their Eyes. (2009)

Juan José Campanella

I'd say skip this one in the theaters and concentrate on the

Millennium-trilogy instead. [UPDATE: Skip The Girl Who Played With Fire. See -- I don't know, maybe I Am Love? I'll look into it...]

It needed a shot of chemistry, and felt more like a TV crime-drama than a film. Campanella is more known for works on TV shows such as: House, Law & Order, Law & Order: Criminal Intent, 30 Rock, Ed, The Guardian... I'm not saying The Secret in Their Eyes is a bad film because it isn't. I am saying that there were much better foreign films last year, especially Oscar-competitor The White Ribbon. And I'm also saying that this felt like a very good TV show, and not an astounding, thrilling, life-changing film.

Saturday, July 3, 2010

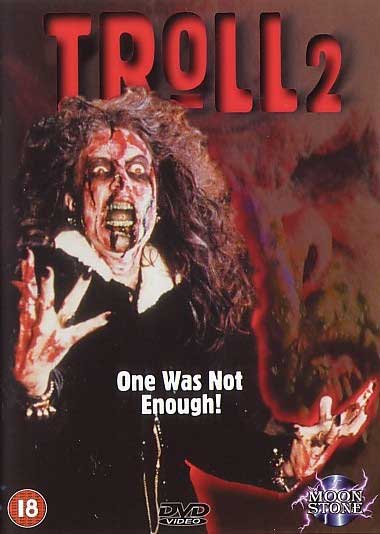

Troll 2. (1990) Claudio Fragasso

This could honestly be the worst film ever made. It has the world's worst idea for a plot, and a script that elevates the ideas to an even greater level of stenchiness; horrible, staged acting which sounds like a grade school play where the lines are robotically repeated ad nauseum; terribly poor camera work and stunning special effects; and for a film entitled Troll 2, it doesn't even have a troll. It's got goblins galore, though, each actor fitting into a fully suited costume with a zipper down the side that shows. It's also got some kind of a witch -- I really couldn't quite figure out why -- and she takes the cake as the most overdramatic stage queen in a role seemingly lifted from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. (One of her shrieks even had a vibrato.)

The film tried to aim for horror, a genre that's been crucified over and over again with countless hacks and misses. But it turns out twenty years later to be suited for a pomo comedy, where we don't wince at the badness but rather laugh at the lost cause, chuckling from our hipster positions. It rakes up five star ratings at Netflix (their highest) with comments telling you it must be seen for its badness. There are conventions in California where crowds gather to watch it, to marvel at film abortion on display.

It works for that crowd. There's really nothing you can do but laugh. There's enough unintended camp that comes from an understanding of the typical conventions and an ability to recognize low-budget failure to take in a viewing two decades later and spit out barrels of laughter. But it probably didn't work when the film first came out -- those audiences must have been shell-shocked.

There's a documentary hitting the big screen later this month called Best Worst Movie in which the actor from Troll 2, now a good looking grown-up small-town dentist who has been hiding Troll 2 from the local community, comes out of the closet about his lurid acting past and even appears as a guest speaker at a California screening. Having had more than a few hacks and misses at creating art myself, I find the notion of this fellow looking back completely fun, and from what I can see in the trailer, he really seems to be a good sport about the whole thing. In preparation for the doc, I wanted to see just how bad Troll 2 really was -- if indeed, as has been claimed, it really is the world's worst movie. (It has been on the bottom of IMDB's

Bottom 100 list and still sits there today at a comfortable #62.)

I love to seek out the good and not the bad. My posts here at Filmsweep are more about the films and ideas I fall in love with. The idea that there was something so hideous in this fellow's past as Troll 2 -- which I assure you is really as hideous as I've made it sound -- but that he can smile about it and celebrate it with a crowd of affectionate scoffers, is an idea that intrigues me. I can't wait to see Best Worst Movie, it's the second highest film I'm looking forward to this summer.

The film tried to aim for horror, a genre that's been crucified over and over again with countless hacks and misses. But it turns out twenty years later to be suited for a pomo comedy, where we don't wince at the badness but rather laugh at the lost cause, chuckling from our hipster positions. It rakes up five star ratings at Netflix (their highest) with comments telling you it must be seen for its badness. There are conventions in California where crowds gather to watch it, to marvel at film abortion on display.

It works for that crowd. There's really nothing you can do but laugh. There's enough unintended camp that comes from an understanding of the typical conventions and an ability to recognize low-budget failure to take in a viewing two decades later and spit out barrels of laughter. But it probably didn't work when the film first came out -- those audiences must have been shell-shocked.

There's a documentary hitting the big screen later this month called Best Worst Movie in which the actor from Troll 2, now a good looking grown-up small-town dentist who has been hiding Troll 2 from the local community, comes out of the closet about his lurid acting past and even appears as a guest speaker at a California screening. Having had more than a few hacks and misses at creating art myself, I find the notion of this fellow looking back completely fun, and from what I can see in the trailer, he really seems to be a good sport about the whole thing. In preparation for the doc, I wanted to see just how bad Troll 2 really was -- if indeed, as has been claimed, it really is the world's worst movie. (It has been on the bottom of IMDB's

Bottom 100 list and still sits there today at a comfortable #62.)

I love to seek out the good and not the bad. My posts here at Filmsweep are more about the films and ideas I fall in love with. The idea that there was something so hideous in this fellow's past as Troll 2 -- which I assure you is really as hideous as I've made it sound -- but that he can smile about it and celebrate it with a crowd of affectionate scoffers, is an idea that intrigues me. I can't wait to see Best Worst Movie, it's the second highest film I'm looking forward to this summer.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)