A Russian Feast for the Eye, for A Black & White Still Winter.

Last month I wrote about Un chien andalou, an avant-garde surrealist sixteen-minute jolt, made in Paris in 1929 by artist Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel in his directorial debut. Around the same time the two were working on that masterpiece, a well-known filmmaker from Russia was working on one of his own: Man With a Movie Camera.

I reference the former because it's as unconventional as the latter, and of interest in pertaining to cinematic shifts at that time in other locked-off portions of the world.

Both were experiments, each in their own way. But whereas Un chien andalou set out to simply "shock the (Parisian) middle class," Vertov's submission looks more noble in its purpose: documenting the daily life of the citizens of Soviet Odessa, capturing life at the start of communism and machinist modernism -- a people at work, at play, and perhaps sometimes in their dreams.

"A Record in Celluloid on 3 Reels," the film advertises its innovative nature from its opening frames, referring to itself as, "A Film Without Intertitles... A Film Without a Scenario... A Film Without Sets, Actors, etc... This experimental work aims at creating a truly international absolute language of cinema based on its total separation from the language of Theater and Literature."

And then like Eisenstein's Odessa Staircase sequence, that famous montage from Battleship Potemkin, lickity-split, we're off to the races. Man With a Movie Camera is edited at a frenetic pace*. The eye can't set on any one image for too long. It's not allowed to. These are perhaps the first films in history that take editing so seriously, and to its extreme. You blink and you've missed something.

But it's not just the editing of Man With a Movie Camera that makes it special. Even in our age of over-classification, with products categorized for groups and sub-groups of people, Man With a Movie Camera is a hard one to pin to any demographic. With no words rendered, it's still a full pictorial documentary. Yet by evidence of its own juxtaposed images, it's as avant-garde as any experimental work. The idea that it is hard to categorize into genre, along with the techniques the film employs (many of which were new in their day), make it a one-of-a-kind event, setting a high bar for any movie that would follow.

In its Wikipedia entry, a writer explains these new techniques:

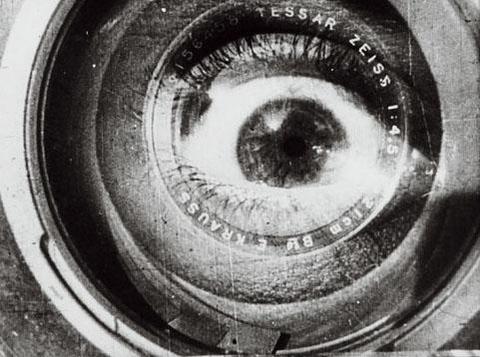

A couple of images, self-explanatory in the idea of how this documentary is also avant-garde:

The self-reflexive nature was also something new -- the idea that the maker can be a part of the creation, as well, and that he's free to reference himself.

None of this is to say that it's easy viewing. After some time, the hardcore edits that once were so energizing can also become tiresome to the eye. Critics at the time complained about the frantic cuts, the fact that Vertov never let them settle and absorb into an image.

But there's a sly wink from Vertov in the film, where he speaks to these critics before they even had a chance to voice an opinion. Somewhere near the middle, we note that the camera man has a hard time taking it all in. In an eye-splintering montage (edits here seem to be running at about a half second or less), we see his eye, and then the city, then his eye, then another shift in focus, back to his eye, and back to the people of the city, and so it goes. It's as if he is identifying with us in this moment, fully acknowledging that yes, it's a lot to take in -- but so is the depth of this city in general.

While not easy viewing, I would call it essential viewing for anyone enamored with the power of film, anyone who wants to understand where our modern concepts came from. It also functions as a historical file for Odessa, an archive of that place and a few other towns nearby.

Any other town which doesn't have a film like this should be envious, desiring something like it for its own.

I had a hard time keeping up with it. I'm somewhat certain that's part of the point. But at only sixty-seven minutes, I can't wait to see it again.

*It's been said that of the over 1700 cuts, Vertov's wife had to select and edit them all together. It's also been said that she was supposed to make some sort of sense of all of these images, deciphering their varying natures and building a sort of "narrative" along the way -- an impossible task to ask of her or anyone else, but she certainly made this into an interesting, sometimes mesmerizing experience.

I reference the former because it's as unconventional as the latter, and of interest in pertaining to cinematic shifts at that time in other locked-off portions of the world.

Both were experiments, each in their own way. But whereas Un chien andalou set out to simply "shock the (Parisian) middle class," Vertov's submission looks more noble in its purpose: documenting the daily life of the citizens of Soviet Odessa, capturing life at the start of communism and machinist modernism -- a people at work, at play, and perhaps sometimes in their dreams.

"A Record in Celluloid on 3 Reels," the film advertises its innovative nature from its opening frames, referring to itself as, "A Film Without Intertitles... A Film Without a Scenario... A Film Without Sets, Actors, etc... This experimental work aims at creating a truly international absolute language of cinema based on its total separation from the language of Theater and Literature."

And then like Eisenstein's Odessa Staircase sequence, that famous montage from Battleship Potemkin, lickity-split, we're off to the races. Man With a Movie Camera is edited at a frenetic pace*. The eye can't set on any one image for too long. It's not allowed to. These are perhaps the first films in history that take editing so seriously, and to its extreme. You blink and you've missed something.

But it's not just the editing of Man With a Movie Camera that makes it special. Even in our age of over-classification, with products categorized for groups and sub-groups of people, Man With a Movie Camera is a hard one to pin to any demographic. With no words rendered, it's still a full pictorial documentary. Yet by evidence of its own juxtaposed images, it's as avant-garde as any experimental work. The idea that it is hard to categorize into genre, along with the techniques the film employs (many of which were new in their day), make it a one-of-a-kind event, setting a high bar for any movie that would follow.

In its Wikipedia entry, a writer explains these new techniques:

This film is famous for the range of cinematic techniques Vertov invents, deploys or develops, such as double exposure, fast motion, slow motion, freeze frames, jump cuts,split screens, Dutch angles, extreme close-ups, tracking shots, footage played backwards, stop motion animations and a self-reflexive style (at one point it features a split screen tracking shot; the sides have opposite Dutch angles).Anything you can imagine -- workers in local factories, crowds in the city street, people brushing their teeth or putting on clothes in the morning or laying their head on train tracks or giving birth -- are mixed into this sixty-seven minute monstrous montage in which the man with the camera is ever-present. He is there capturing all of the land's happenings, and creating a few off-kilter images of his own. We follow him in a car, we see him dancing high on I-beams with his tripod, ready to film -- we see his eye in the lens itself, showing us that he sees what we see, but he wants to show it to us in a very different way.

A couple of images, self-explanatory in the idea of how this documentary is also avant-garde:

The self-reflexive nature was also something new -- the idea that the maker can be a part of the creation, as well, and that he's free to reference himself.

None of this is to say that it's easy viewing. After some time, the hardcore edits that once were so energizing can also become tiresome to the eye. Critics at the time complained about the frantic cuts, the fact that Vertov never let them settle and absorb into an image.

But there's a sly wink from Vertov in the film, where he speaks to these critics before they even had a chance to voice an opinion. Somewhere near the middle, we note that the camera man has a hard time taking it all in. In an eye-splintering montage (edits here seem to be running at about a half second or less), we see his eye, and then the city, then his eye, then another shift in focus, back to his eye, and back to the people of the city, and so it goes. It's as if he is identifying with us in this moment, fully acknowledging that yes, it's a lot to take in -- but so is the depth of this city in general.

While not easy viewing, I would call it essential viewing for anyone enamored with the power of film, anyone who wants to understand where our modern concepts came from. It also functions as a historical file for Odessa, an archive of that place and a few other towns nearby.

Any other town which doesn't have a film like this should be envious, desiring something like it for its own.

I had a hard time keeping up with it. I'm somewhat certain that's part of the point. But at only sixty-seven minutes, I can't wait to see it again.

*It's been said that of the over 1700 cuts, Vertov's wife had to select and edit them all together. It's also been said that she was supposed to make some sort of sense of all of these images, deciphering their varying natures and building a sort of "narrative" along the way -- an impossible task to ask of her or anyone else, but she certainly made this into an interesting, sometimes mesmerizing experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I like to respond to comments. If you keep it relatively clean and respectful, and use your name or any name outside of "Anonymous," I will be much more apt to respond. Spam or stupidity is mine to delete at will. Thanks.