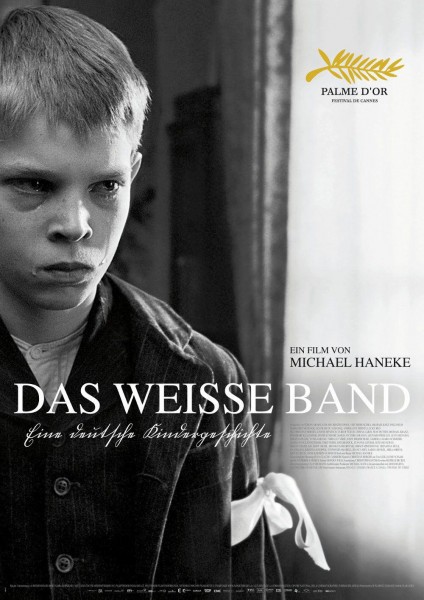

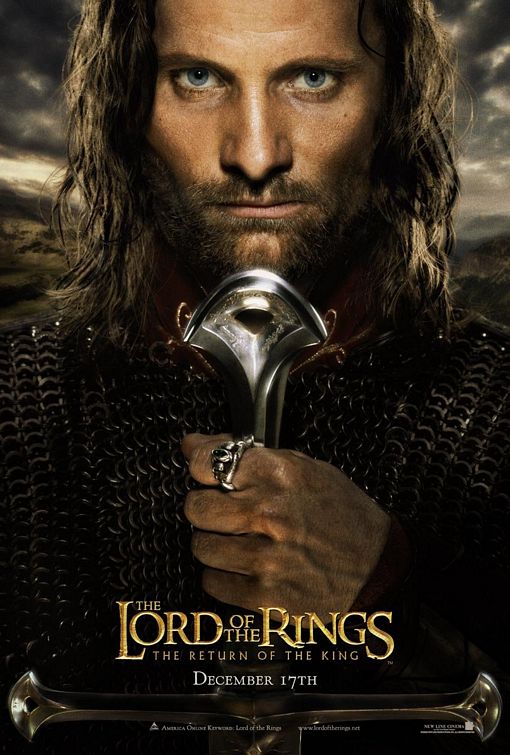

Almodóvar's All About My Mother (1999)

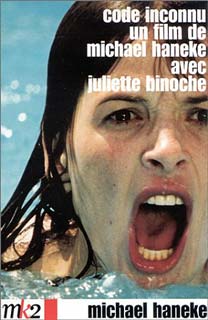

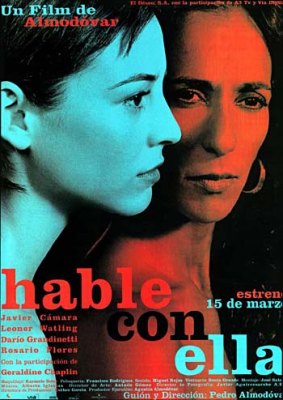

Almodóvar's Talk To Her (2002)

At the moment I'm trying to catch up on two artists I've neglected until recently.

The first, Pedro Almodóvar, I only neglected because there just isn't enough time for every film in the world, much as I wish there were. It turns out I pretty much agree with everyone else -- he's a genius film director, with a heavy emphasis on character study, particularly female, and an emotionally alluring narrative drive. He's particularly fond of studying the nature of women in general -- how they relate to one another, how they function in different families, how they react, how they support, how they love. He likes to bump characters into each other who ordinarily would not mix, and then we get to watch as they interplay with each other and grow in their social support.

So I've seen my first two Almodóvar films, and they are

All About My Mother, and

Talk To Her.

All About My Mother is the 2000 Oscar winner for Best Foreign Language Film. It's about a grieving mom, a transvestite, a pregnant nun and a well-known theater actress, and how their lives intersect and entwine. It ends with Almodóvar dedicating the piece to his mom and all women everywhere. He relishes in the creation of "the woman," and he builds the film as a sort of tribute to her many stages. He shows us, too, how women build communal and familial homes in one another when separated, whatever the reason, from their own families.

Talk To Her is the strikingly unconventional story about two women -- a dancer and a bullfighter -- who end up in comas in hospital rooms as neighbors. As their families try to relate to them in their state, we see them continue their relationships with the women even when they doubt they will open their eyes again. To say more here would be giving way too much away about this wonderfully engossing spanish film. This one just has to be seen to be understood.

The second neglected artist I want to mention is a writer named

Dan B. Allender, PhD. I haven't heard of him until recently. He was brought to my attention from a friend who excitedly approached me, saying, "You've got to read this book,

To Be Told! It is awesome!" And he went on and on about it. The book is in high demand, and it took a little while for the library to track down a copy. As soon as I dove into it, I was sold.

To Be Told is a book about

Story, that is, "story" with a capital "S". Allender proposes in

To Be Told his idea that your life is an important story of God's design; that no matter where you're at in life, you are always co-authoring the Story of your life with God. Yours is a unique story worth living out and sharing with others; it has the potential to be a blessing to listening ears.

It was odd timing for my friend to approach me with this particular book at this particular time. Lately, the thought of writing down some thoughts regarding

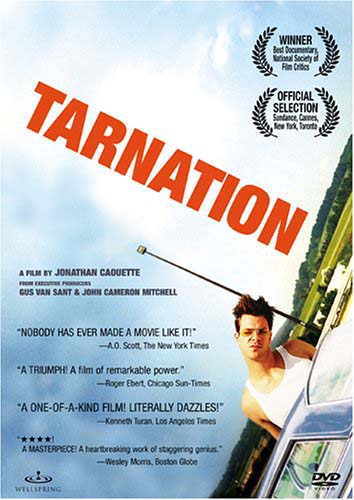

My Existence On The Planet Earth has been at the front of my mind, anyway. I do, after all, have a truly unique story. It's not quite as unique as the writer's unfathomable story in

Running With Scissors, or as crazily depressing as the nutty family in

The Squid and the Whale, but it's a story, nonetheless, one that is mine, but shared with my family and friends and acquaintances along the way. It's a wild ride, with some crazier-than-usual moments. It is fun, and it's certainly not typical in any way that I know. You can call my story whatever you want, but typical, it ain't.

I'm the only person I know who has been a preacher's kid, a student, a missionary, a musician (a "mini-Rock Star" in the best moments of that season), a minister, a guy with a pencil in his shirt in a cubicle, a worker at a doctor's office, and a guy stocking shelves for a world enterprise that I hate. I'm a Christian (for lack of a better word), a lover, a father, an alcoholic, and the most broke person with the most hope you've ever met. (I am turning 40 this spring and right now there are $300 Big Bucks in the bank. That's it. No retirement fund, no 401K. There's nothing else, unless I sell a few vintage guitars. And honestly, I have more hope than ever before.)

I'm also the only person I know who got in a fight with a car wash -- and won! -- I kicked the crap out of that car wash!... And I'm the only person I know who has gone

into a country with a group of friends the day after it was militarily taken over.

I've faced total abandonment, divorce, rehab, anxiety, depression and defeat -- and what's been proven to me in some of the hardest moments I've faced is that at your lowest point, God will meet you. Some of us just need to bottom out to

get it.

So my Story really is unique. I mean, everything I just listed was all off the top of my head. There's so much more! I'm the only American I ever met that played guitar and sang in a duet on The Miss Albanian show live in Albania, to over three million people on TV. See? I told you there was more. (Instant. Albanian. Fame!)

The timing on my friend giving me the Allender recommendation when he didn't know I'd already begun my memoir is odd. Some might call it a coincidence. I've given up on coincidences. Once you've said a prayer and seen a coincidence, only to offer another prayer and get a coincidence, after one more prayer and then once again an almost expected coincidence... Well, you get it. You see a bit more to it than just "coincidence."

But I still admit I'm intimidated at the thought of trying to write about "me". Writing an entire book about "me". I'm not writer, but I've felt that this is something I'm supposed to do -- it has been proven over and over through a series of "coincidences," and it's God ordained. It's more than just a sense. It's a fact in my heart. I've had an outline and a few rough drafts of chapters for three or four months now. But Lord knows, I will need an editor. (If you've read this far I'm sure you feel the same.)

Allender has this idea that all good stories are built on a certain kind of narrative arc. That at the beginning, you have peace.

Shalom. It's that time when everything is as it is supposed to be, that moment when you're at one with yourself and your place in the earth.

But something enters into this sort of Eden, this peaceful placed called Shalom. And that is

tension. Tension brings with it: Frustration. Tragedy. A shattered Shalom. Ugliness. Sin. Reality. Tension is unavoidable, and the reason it propels a good story is because it's a reflection of how life truly works -- certain hardships are unavoidable, and that's life. How good the story, or

Your Story is, depends on how you choose to struggle through the hardships, the choices and decisions you're forced to make, the bad ones along with the good. According to Allender, the goal of your story is to determine what kind of an ending, or what kind of

denouement you are going to co-author with God as your writing buddy.

I like this. It's one of the most simple structures for explanation I've seen, and it seems to make perfect sense. If this is all it takes to make a Good Story, I know I have a wowza of a story to tell.

So I've been reading Allender and tracking down the films of the gifted filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar. Most Americans know him even if they don't because all of the spanish films in which you find that righteous babe Penélope Cruz are Almodóvar's films. Essentially, he discovered her years ago, and now they are best friends. They make films together, they have coffee together -- she has said in an interview that when he's feeling depressed, she likes to be the "nurse" that gets him through it. So they're best friends. No more, no less. The relationship goes no further, because Almodóvar is gay.

In watching

All About My Mother and

Talk To Her, I've stumbled upon a filmmaker that, in my mind, is utterly brilliant. His cinematography is scrumptious, and his storylines are simply fun and peculiar. Perhaps "quirky based in classical" is a good way to describe them. He loves exploring the nature of The Woman, and he endlessly drops little nods to his love for world cinema. For instance, the sensational

All About My Mother is actually a nod to the classic

All About Eve, which even plays as a film within the film, setting the tone for much of the role-playing the women end up grappling with.

Almodóvar might get along quite well with Allender, too, for he really knows how to tell a good story:

Shalom. Tension. Risk. Disaster. Desire. Honesty. Denouement. The films ride on an emotional roller coaster that is rigid with such precise tension that you can't help but hope for a good end for its characters. You really want to see a return to that peace, that Eden. You inwardly suffer for these characters to return to Shalom.

There are several Almodóvars now lined up in my DVD queue. It'll be interesting to continue comparing them to Allender's ideas on Good Story. It'll also be interesting to compare them to my Story, and whether or not I can honestly tell it well. Honesty, it would seem, is really all that it takes.

But if you think there's a tension around watching or reading a good story, try experiencing it and then writing for a while. It's not as easy as you might think. There are bumps to getting that pain out and onto paper. Good Story hurts.