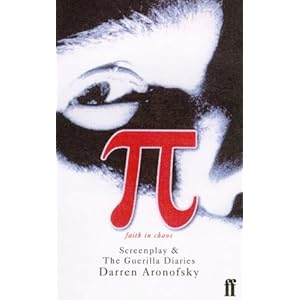

This is only my second book review here at Filmsweep, but I had so much fun with this quick, fun read, I just had to share the experience.

It's about the humble beginnings of that knock-out film Pi, the black and white sci-fi mind melter that launched Darren Aronofsky's career. You know Aronofsky, right? You've probably heard of Requiem For a Dream, The Fountain, The Wrestler, or the upcoming Natalie Portman film, The Black Swan. All of these were made post-Pi, on big budgets, long after Aronofsky got the attention of the film industry in '98 by bringing it to Sundance, where it premiered, and got him the prize for Best Director.

What a great moment that must have been. The diaries don't extend that far, in fact they only lead up to four days in front of that moment. But knowing how he toiled for two to five years, depending how you count, knowing his dedication to the project when the funds weren't there and how he labored to keep everything afloat, the win at Sundance must have been his life's most fulfilling moment.

It's neat to see how Pi was conceived, launched, formed into a collaboration of some thirty workers and whittled down to five reels of 35mm film. As the diary progresses, some of the members of the team have to leave the collaboration and move on -- some very late in the project, which frustrates Aronofsky to no end. In his own words he confesses the desire to lash out, but knows it won't do any good. As an up and coming director he knows his goal, which is not just Pi, but directing greater, more massive and well funded films years from now. He is very smart to contain himself in restraint against the enormous feelings inside that beg him to lose his cool.

The film Pi has so many philosophical and spiritual ramifications that have created mounds of discussion in film groups for the past twelve years. The book dives into just a little bit of Aronofsky's spirituality, answering some of the common assumptions that are made by viewers of the film. He doesn't necessarily believe in a God that has a face and a name, but like Max, the main character in Pi, he sees patterns in the universe -- even in the microverse and how they compare when contrasted with universal design -- that lead him to believe in, well, in something. At various points on the set he has the entire crew gather in a circle and hold hands in a prayer-like stance. They don't really offer a prayer as much as submit to the idea of unification. His exact words describe a group moment of "economic and artistic partnership, a socialist collective."

Never mind that Max is half insane -- he and Aronofsky are undeniably linked. Max's graphing of the stock market for emerging numbers is akin to Aronofsky's musings on nature's shapes and connectivity: he finds it fascinating that our DNA and the Milky Way are (by his estimation) so visually connected. "Personally," he says, "I don't think it's this end-all universal form connected to God. But I do think it's awfully strange that our smallest ingredient (DNA) and our largest macro-structure (The Milky Way) are so similar in shape."

At the end of Pi, Max is having an existential moment. Viewers often muse that it is very similar to an existential moment he had at the beginning of the film, but at the beginning he was in a state of crisis, whereas in the end his state is more esoteric. The diary describes it as a moment when Max is fully present -- in the "here and now" -- for the first time, at the end of the story. I chuckled a bit reading those lines, thinking that Henri Nouwen would have loved this. He may have found a rich tradition of Christian spirituality in simply sitting still, observing, meditating, listening. It's hard to say whether Max's cyberworld really goes this far or not, and Aronofsky doesn't really say. It's actually one of the more intriguing mysteries that keeps your eyes glued to both the film and the written diaries.

The second part of the book is the actual script for the film. If you've seen and enjoyed Pi, even if it was years ago, this is a highly enjoyable read. As you glide along the words of the script your memory wanders back to those stark, sometimes horrible and freaked out black and white images -- and you remember in writing the fascination the film has in mathematical code, number theory (specifically the number 216), spirals, the Torah, ancient Kabbalah texts, and the anomalies of human error.

I can't say I'm a great reader or that I read a lot of books, but if they were all as much fun as this one I'd aim to read more.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

I like to respond to comments. If you keep it relatively clean and respectful, and use your name or any name outside of "Anonymous," I will be much more apt to respond. Spam or stupidity is mine to delete at will. Thanks.