If you find yourself taken this weekend with the documentary-style of The Last Exorcism but feel let down in its Rosemary's Baby run-on, cliched finale -- and if the vérité feels far more fun than demonic images that are elements of fraudulent Hollywood rather than anything remotely spiritually real -- then perhaps you'll be more interested in the film The Last Exorcism riffed on to get noticed, a film which has a similar phony preacher bringing deliverance and counting the cash, but is very much reality and filmed with a concentrated focus.

In going through thoughts on The Last Exorcism, I saw that a friend linked to some writing I did when I first saw Marjoe. It was fun to read my passionate response to the years-old doc. The following was quickly written, and probably not as well thought-out as when I sit down to blog here at Filmsweep. But it had excitement, a sense of finding something unique, and it feels like it convinces that Marjoe is worthy viewing nearly four decades after it was made.

As the next "Non-lollipop Docs" column will be waiting 'til the end of next month, consider this a heads-up on a great documentary that still remains somewhat overlooked.

_________________________________________

Holy guacamole, and great tongues of fire!

I feel like I just a had a "religulous" experience. I tripped on Jesus music, revival tent ministry and mass manipulation all at once! I also came away feeling uplifted and swindled, both at the same time.

(Gee, I wonder whether I might be back in the throes of Pentecostalism.)

The life of the evangelist Marjoe Gortner has been mentioned before -- both here, where I first heard of him from the Lonnie Frisbee documentary, and here, in the Houston Chronicle's writeup on Saved -- but there's no dedicated thread to the 1973 Oscar winning doc. So here we go.

The raw footage of Marjoe as a four-year old boy playing "Onward Christian Soldiers" on his accordion, pronouncing fire and brimstone sermons as the prodigy "boy preacher," and even (GASP!) marrying a couple in a church as a six year-old, really set the tone for grasping Marjoe's unique and problematic thinking. It's hard to believe he grew up in these vast Christian settings, coached by his mom to wail and preach, not even acquiring a real faith but just parroting the system in which he was taught how to succeed. He became a showman at a very young age, a charlatan with enough skills to make money for his parents (he claims over three million dollars, money he never saw) and also performing in this way to receive his parents' love. It was a performance-based love; Marjoe never felt he was loved for anything more than the green he brought in and the hanky-waving fervor he jerked out of crowds in preaching to adults all around him.

Fast forward some twenty-or-so years, and now we see Marjoe ready to come out of the closet, so to speak. Like "Candid Camera", or the wizard behind the curtain, Marjoe brings a full film crew with him as he tours the Pentecostal church circuit of the early 70s in prep to expose his true identity. The crew is fully aware of who he is and the business of what he is doing -- the church people will find out sometime after the documentary is released.

It's really interesting to watch Marjoe as he teaches the film crew how to conduct themselves as they film the (loud and "powerful") worship services. He instructs them not to freak out when people begin uttering strange languages -- he describes tongues as the grand zenith of a Pentecostal worship service, and even instructs the cameraman to make sure he zooms in when someone is being "filled with the Holy Spirit".

He also instructs his crew to not smoke, to get haircuts and to sexually stay away from the believers. "You cannot get involved with these chicks at all... That's a rule that I established," Marjoe says. "I never take out a girl from the church or in the church. I stick with airline stewardesses."

I believe there were two reasons for the sexual warning: The first, because for years he'd been "ministering" and he wasn't yet ready to risk his credibility among the church people. The second, and this is debatable, is that Marjoe really does care about the born-agains in his audience. He goes so far as to claim that part of the reason he wants to make the film is so that some in these evangelical communities might grow. When the crew asks him, "What will happen when they find out?" Marjoe replies, "Well, I'm hoping that they will see, you know, that it's not necessary to look to some person to like, you know, jerk you off -- to get off -- and put your belief in."

The music plays a huge part in every revival meeting setting. When people are whipped into this holy, hypnotic, trance-like musical bliss, they are, at the end of the night, more emotionally ready to empty their wallets into Marjoe's baskets. In one of the most blasphemous scenes -- the one incorporated into the Lonnie Frisbee film -- Marjoe is seen dumping a huge wad of money on his hotel bed and "praising Jesus" for it.

I guess the use of music to stir up the crowd is nothing new, especially in relation to how most churches want at least a bit of this stirring incorporated into their services, and how tribes and cultures have always used music in their rituals from the beginning of time. But somehow, I don't think there were plates passed at the end of a tribal drum circle thousands of years ago. Back then music may have led more to the sexual cravings, which makes just as much sense as the passing of the plate... Then again, maybe the sex in those settings wasn't typically considered immoral, which would place these evangelical fakes as more immoral than other cultures and generations similarly using music in religious rituals... Hmm. I'll still be mulling that thought over.

I did feel sorry for the good church folk as Marjoe strutted the aisles proclaiming the good news, knowing he didn't believe a word of it. But the optimist in me wondered how many times Marjoe may have been used by God and didn't even know it. Having just come off the Lonnie Frisbee viewing, in which God seemingly brings salvation to a kid on LSD, who then brings thousands to Christ while still struggling to get off the drug, one wonders if it's not possible that God can work through any broken vessel He chooses. In Marjoe, it is a hypocritical, unbelieving one.

There was something in me that liked the freedom with which the congregants were able to blatantly dance and worship in front of their Creator. So childlike, so trusting. So innocent and really in love with God and in desire of His goodness. I wish for these kinds of worshippers that they could have all of this without the background blows of exploitation and manipulation. Having come from (some of) this background myself, and having left it long ago, I've come to the conclusion that my wish will never come true. Sadly, there's just too much humanity and desire for power in us needy, greedy humans.

Regardless, I found that I liked the Marjoe character in all of his hypocrisy and inauthenticism much more than the preacher in one of the tent meetings who, over and over, kept reminding us that once he really dedicated his life to God he was given a Cadillac. Eek. I didn't like his message at all. I'd take Marjoe's fake message over that guy's real one any day.

This is a Netflix four out of five stars. It would be four-and-a half, but Netflix doesn't allow 1/2 stars. The reason it falls short of a FIVE is that the film needed to delve deeper into Marjoe's adult relationship with his parents. I really wish we'd have been offered more of a glimpse of the whole family, all grown up. When his dad shows up to be in a service with him, we never fully know whether his dad is a fake or a real believer... And his mom isn't even heard from in Marjoe's adult life. Is she dead? Did they divorce? Where is she now? We just don't know. And his dad mentions that Marjoe is the fourth generation evangelist in their family, so what I would have liked to know is, Was great-grandpa that was a missionary to Liberia a fake too? And was grandpa a fake in whatever evangelism he did, or was he the real deal?

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

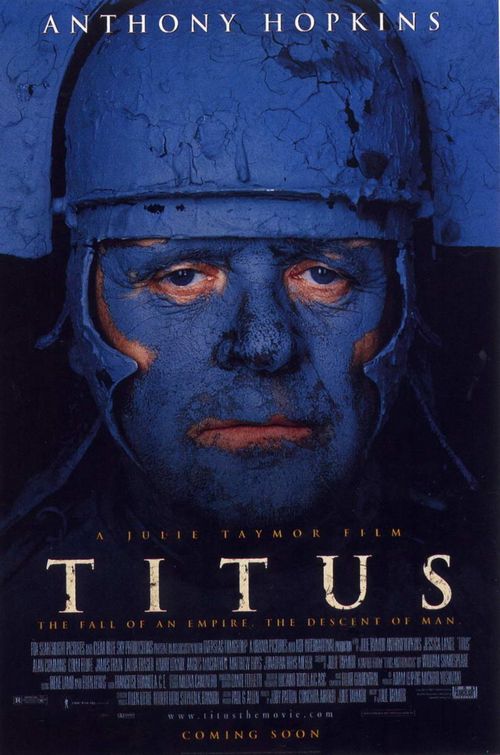

Titus. (1999) Julie Taymor

In a few months you'll be hearing quite a bit about The Tempest. Based on the director and her proven results with Shakespeare, in both theater and in film, I have little doubt it will be one of the great films of 2010. Time will tell, but Julie Taymor has already shown what happens when she tackles a screenplay and directs a movie for Sir William. She directs with the kind of fire and insight his works need to relay the furious and compelling nature of his emotive, astonishing language.

Not that I'm a Shakespeare aficionado, because I'm not. I readily admit I'm nowhere near smart enough to try and cop to that. I do, however, see more movies than most and I recognize sheer ambition and swoon when it comes my way. Titus is proof of what happens when Shakespeare lands in daring, ambitious hands. It is riveting to behold -- gargantuan, chaotic: FULL ON. I watched it again recently because I am excited for The Tempest, but what I found in Titus was the same brilliant work I saw years ago.

A little boy with an "unknown comic" paper bag over his head plays at a crowded kitchen table stuffed with all his crazy toys. A blaring TV with nothing in particular fills in a noisy background as his playing voice quickly rises, drowning out the blaring TV, turning violent. It's almost as if he suddenly hates the toys and needs to rebuke them for their sin. They, too, are out for blood and want to fight -- fight with each other and with him. He screams at them, pours his food all over them, crashes them into one another and his dinner. A toy soldier scratches at the surface of the table trying to crawl away in fear.

The boy is on a rampage now. Violence erupting his small being spills into the reality of the room, shaking the foundations of the whole house. The violence becomes too much as it pounds and pounds.

He realizes it has come to life. The house may very soon crumble. The growing, dark setting overwhelms him -- he is panicked at the thought of the toys and the violence he has created. The room shakes and finally explodes as he covers his ears in fear.

He is whisked away and carried down a hole ala Alice into Wonderland by a clown that doesn't look like a clown. Down the hole he goes but not before we see his saddest look, and tears streaming down his scared face. Did he really create this violence? Could his imagination become physical? Has it come back to haunt his very play? Is he innocent, as we might think, just a child doing what a child does, or has he brought malevolent harm that he wishes he could take back?

Down the hole he goes into the Roman world of Titus Andronicus, who will introduce him to similar perils, albeit political. The child will be a silent observer, a mute witness for the first half of this story, to blood upon unrelenting blood, until he can take it no more and must enter the story himself. He becomes little Lucius, the grandson of Titus the hero, the general who has come home with the spoils and loot of war, only to be spoiled and looted himself.

Is there a better way to launch the introduction to arguably one of Shakespeare's most disturbing and dark works than with this innocent bystander with a history of his own -- a child, no less, carried to Rome to observe? And when observing the most hideous and corrupt actions in human nature, could anyone better deal with resolving the violence he has seen?

Bringing the silent observer the way Taymor does and then turning him into the character of Titus's grandson is an affecting choice in the midst of this blood-thirsty world. We need someone there to remind us of innocence. We need someone there that can watch, while we observe.

In a matter of hours, in some questionably wrong but understandable choices of allegiance, Titus (Anthony Hopkins) goes from war hero to outcast, dispossessed from his country, cut off from his people and his family. Maybe for the first time in his adult life, he is utterly isolated, completely alone. To make matters worse his enemy Tamora, Queen of the goths (Jessica Lange) is strangely promoted from slave to Queen of the empire -- she will easily infect young King Saturninus against Titus, and his sons and daughter are going to pay the ultimate price in revenge.

In terms of the rest of the plot, it's the story of their feud -- it's the Hatfields vs. the McCoys dressed as warring politics in ancient Rome. In terms of Shakespeare and the way he tells the story -- oh! The language! I cannot describe how amazing it is. Time doesn't make any of this old language grow more "old," but greater, more rich, more poetic and able to dig in. It connects even with modern audiences and contemporary ears. This is a story that was originally read for its language -- you will be richly rewarded if you watch with the subtitles on.

In terms of what Taymor has done with all this, her approach is very similar to Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes only a few years before. The films have in common a blending of traditions -- they each carry an ancient/modern approach to the screen. But while the guns and shooting in Luhrmann's film come off as vain and gimmicky, the vehicles and costumes and the whole design of visuals in Titus are always an allegory that's tangible, within reach. It is as entertaining to look at as it is to consider.

In fact, I know I've talked about it already a hundred times this year, but going back a decade and watching Titus brings back memories of last year's masterpiece, Vincere. It is that grandiose, that daring, it is that willing to take risks, and has that ability to believe in itself (and achieve in itself!). These are all the reasons it brings success in such large measure. Even the imperial Roman art and neo-classical architecture are where the two films relate so well. Characters in both films, too, are intoxicating, as is the camera's ability, which is unyielding.

But Titus is written by Shakespeare.

And that is clearly what sets is apart.

Titus Andronicus, as played by Hopkins and Lange, is an incredible spectacle of blood-lust and power -- and the child that was so frightened of the violence he created brings one of the best, most artistic endings imaginable.

I'm so glad I was able to see this again, and now I'm more excited than ever for The Tempest. We'll see how Helen Mirren's female Prospera will add to the Taymor/Shakespeare tradition!

Not that I'm a Shakespeare aficionado, because I'm not. I readily admit I'm nowhere near smart enough to try and cop to that. I do, however, see more movies than most and I recognize sheer ambition and swoon when it comes my way. Titus is proof of what happens when Shakespeare lands in daring, ambitious hands. It is riveting to behold -- gargantuan, chaotic: FULL ON. I watched it again recently because I am excited for The Tempest, but what I found in Titus was the same brilliant work I saw years ago.

A little boy with an "unknown comic" paper bag over his head plays at a crowded kitchen table stuffed with all his crazy toys. A blaring TV with nothing in particular fills in a noisy background as his playing voice quickly rises, drowning out the blaring TV, turning violent. It's almost as if he suddenly hates the toys and needs to rebuke them for their sin. They, too, are out for blood and want to fight -- fight with each other and with him. He screams at them, pours his food all over them, crashes them into one another and his dinner. A toy soldier scratches at the surface of the table trying to crawl away in fear.

The boy is on a rampage now. Violence erupting his small being spills into the reality of the room, shaking the foundations of the whole house. The violence becomes too much as it pounds and pounds.

He realizes it has come to life. The house may very soon crumble. The growing, dark setting overwhelms him -- he is panicked at the thought of the toys and the violence he has created. The room shakes and finally explodes as he covers his ears in fear.

He is whisked away and carried down a hole ala Alice into Wonderland by a clown that doesn't look like a clown. Down the hole he goes but not before we see his saddest look, and tears streaming down his scared face. Did he really create this violence? Could his imagination become physical? Has it come back to haunt his very play? Is he innocent, as we might think, just a child doing what a child does, or has he brought malevolent harm that he wishes he could take back?

Down the hole he goes into the Roman world of Titus Andronicus, who will introduce him to similar perils, albeit political. The child will be a silent observer, a mute witness for the first half of this story, to blood upon unrelenting blood, until he can take it no more and must enter the story himself. He becomes little Lucius, the grandson of Titus the hero, the general who has come home with the spoils and loot of war, only to be spoiled and looted himself.

Is there a better way to launch the introduction to arguably one of Shakespeare's most disturbing and dark works than with this innocent bystander with a history of his own -- a child, no less, carried to Rome to observe? And when observing the most hideous and corrupt actions in human nature, could anyone better deal with resolving the violence he has seen?

Bringing the silent observer the way Taymor does and then turning him into the character of Titus's grandson is an affecting choice in the midst of this blood-thirsty world. We need someone there to remind us of innocence. We need someone there that can watch, while we observe.

In a matter of hours, in some questionably wrong but understandable choices of allegiance, Titus (Anthony Hopkins) goes from war hero to outcast, dispossessed from his country, cut off from his people and his family. Maybe for the first time in his adult life, he is utterly isolated, completely alone. To make matters worse his enemy Tamora, Queen of the goths (Jessica Lange) is strangely promoted from slave to Queen of the empire -- she will easily infect young King Saturninus against Titus, and his sons and daughter are going to pay the ultimate price in revenge.

In terms of the rest of the plot, it's the story of their feud -- it's the Hatfields vs. the McCoys dressed as warring politics in ancient Rome. In terms of Shakespeare and the way he tells the story -- oh! The language! I cannot describe how amazing it is. Time doesn't make any of this old language grow more "old," but greater, more rich, more poetic and able to dig in. It connects even with modern audiences and contemporary ears. This is a story that was originally read for its language -- you will be richly rewarded if you watch with the subtitles on.

In terms of what Taymor has done with all this, her approach is very similar to Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes only a few years before. The films have in common a blending of traditions -- they each carry an ancient/modern approach to the screen. But while the guns and shooting in Luhrmann's film come off as vain and gimmicky, the vehicles and costumes and the whole design of visuals in Titus are always an allegory that's tangible, within reach. It is as entertaining to look at as it is to consider.

In fact, I know I've talked about it already a hundred times this year, but going back a decade and watching Titus brings back memories of last year's masterpiece, Vincere. It is that grandiose, that daring, it is that willing to take risks, and has that ability to believe in itself (and achieve in itself!). These are all the reasons it brings success in such large measure. Even the imperial Roman art and neo-classical architecture are where the two films relate so well. Characters in both films, too, are intoxicating, as is the camera's ability, which is unyielding.

But Titus is written by Shakespeare.

And that is clearly what sets is apart.

Titus Andronicus, as played by Hopkins and Lange, is an incredible spectacle of blood-lust and power -- and the child that was so frightened of the violence he created brings one of the best, most artistic endings imaginable.

I'm so glad I was able to see this again, and now I'm more excited than ever for The Tempest. We'll see how Helen Mirren's female Prospera will add to the Taymor/Shakespeare tradition!

Monday, August 23, 2010

1981. (2009) Ricardo Trogi

What does it take to find a friend? What does it take to be a friend? What can you give, or give up, or give into in order to influence the acceptance of a friendship?

Ricardo Trogi (and you can pronounce his surname any way you want but you'll probably still get it wrong) has a stash of Playboys -- or so he says -- and suddenly the eighth grade click he wants in with are giving him their full attention. When you're young, you use what you have. Kids sharing Playboys probably go back to the invention of Playboys. Ricardo's problem is that he doesn't have anything -- the Playboys, the right clothes, a Walkman.

The character, director and narrator are the same. We see Ricardo as a boy, a simple materialistic, not-quite prepubescent teen who wants things he sees in catalogs but has to bug mom and dad for the money. As he navigates the monetary disciplines at home he also spins in a web of Junior High lies. The lies help him form bonds of friendship. Again, we go back to the strength of that tie.

The director/narrator looks back to a time when moving to a new school produces the most profound kind of social fear, when having your arm unnoticeably touched by a pretty girl caves you in to a months-long spree of hormonal rush, and when fear of being noticed in your family -- ie, mom and dad -- make you close your eyes at night and escape into dream lands of fantasy.

It's a fun story. And it is very playful, and quite cute, too -- but sometimes a little too much so. A little sap would have been good in places, but there's a lot of sap on the train with the rest of this fun. The film reminded me of a less-creepy Léolo or a happier, french-speaking Stand By Me, with a touch of the sibling rivalry of E.T. and a small hint of Roberto Benigni's bond with his son in Life Is Beautiful.

And while 1981 isn't exactly as good as any of the films I've just mentioned, it is worth watching, particularly for the last six or eight minutes which are entirely rewarding. Dead-on with real life, the way life works as a lying eighth grader who is bargaining in every relationship he has, the last few scenes close in such a strong way that it makes the proceeding 94 minutes worth the investment.

There's a curious, sad, and possibly quite true moral as Trogi shares about the Jr. Hi experience towards the end: "It happened 26 years ago and I still obsess about it. What was I thinking? The damn truth only works if everyone's telling it."

The quote feels like one of those truths where you wish it weren't true. The thought of it goes against faith in God, or the Bible, or even humanity in general. But you know what? Hate to say it -- he's right. If you cop to your pretend side and no one else joins in, you're not dragging things into the light which will somehow make your life more whole, real, or better -- you're only giving up yourself to liars who will eventually plow you down.

I'm walking away on a serious note to a film that really was light-hearted. I can't tell if that's me or the film. Maybe it's a little bit both.

Ricardo Trogi (and you can pronounce his surname any way you want but you'll probably still get it wrong) has a stash of Playboys -- or so he says -- and suddenly the eighth grade click he wants in with are giving him their full attention. When you're young, you use what you have. Kids sharing Playboys probably go back to the invention of Playboys. Ricardo's problem is that he doesn't have anything -- the Playboys, the right clothes, a Walkman.

The character, director and narrator are the same. We see Ricardo as a boy, a simple materialistic, not-quite prepubescent teen who wants things he sees in catalogs but has to bug mom and dad for the money. As he navigates the monetary disciplines at home he also spins in a web of Junior High lies. The lies help him form bonds of friendship. Again, we go back to the strength of that tie.

The director/narrator looks back to a time when moving to a new school produces the most profound kind of social fear, when having your arm unnoticeably touched by a pretty girl caves you in to a months-long spree of hormonal rush, and when fear of being noticed in your family -- ie, mom and dad -- make you close your eyes at night and escape into dream lands of fantasy.

It's a fun story. And it is very playful, and quite cute, too -- but sometimes a little too much so. A little sap would have been good in places, but there's a lot of sap on the train with the rest of this fun. The film reminded me of a less-creepy Léolo or a happier, french-speaking Stand By Me, with a touch of the sibling rivalry of E.T. and a small hint of Roberto Benigni's bond with his son in Life Is Beautiful.

And while 1981 isn't exactly as good as any of the films I've just mentioned, it is worth watching, particularly for the last six or eight minutes which are entirely rewarding. Dead-on with real life, the way life works as a lying eighth grader who is bargaining in every relationship he has, the last few scenes close in such a strong way that it makes the proceeding 94 minutes worth the investment.

There's a curious, sad, and possibly quite true moral as Trogi shares about the Jr. Hi experience towards the end: "It happened 26 years ago and I still obsess about it. What was I thinking? The damn truth only works if everyone's telling it."

The quote feels like one of those truths where you wish it weren't true. The thought of it goes against faith in God, or the Bible, or even humanity in general. But you know what? Hate to say it -- he's right. If you cop to your pretend side and no one else joins in, you're not dragging things into the light which will somehow make your life more whole, real, or better -- you're only giving up yourself to liars who will eventually plow you down.

I'm walking away on a serious note to a film that really was light-hearted. I can't tell if that's me or the film. Maybe it's a little bit both.

Sunday, August 22, 2010

Paris. (2009) Cédric Klapisch

Titus will no doubt be written about this week.

Paris turned out to be a wonderful little movie about a sister that moves in with her dying brother, bringing her children to his home to take care of him while he awaits a possible heart donation. The film has a stellar cast, which is lead by Juliette Binoche, who, if she's ever turned in a clunker of a performance, I'm not aware of it. Over the last twenty(?) years, she simply amazes on every acting level. Romain Duris (Thomas Seyr in The Beat That My Heart Skipped), François Cluzet (Alexandre Beck from Tell No One), Albert Dupontel (Irréversible and A Very Long Engagement), and Mélanie Laurent (Shosanna in Inglourious Basterds) are only the beginning of other great names involved.

But I can't say enough about Binoche. She is, as always, engrossing. There are several scenes that are only between ten and thirty seconds where she barely says a thing, yet expresses at least six or seven kinds of emotion with the sheer power of her face and eyes. She is easily one of my favorite actresses on the planet, as she's constantly proven she can handle any role (Blue and Code Unknown are the obvious stand-outs but the recent Disengagement comes to mind too). And the thing that is so cool about Juliette Binoche is that she is not some kind of seductress or pin-up gal. She is simply a real woman, who finds these amazing real roles and puts everything she has into it. Love her. Love her!

The title of the film is the setting of the film, which is also a love letter to the city and its inhabitants. Klapisch gets up close and personal as we travel the city streets, running into all kinds of characters from every walk of life, and seeing them in parallel story telling -- lives that don't necessarily intersect, but bump up against one another nonetheless.

This is a good one to watch with your honey bunny.

Thursday, August 19, 2010

When You're Strange. (2009) Tom DiCillo

There are so many reasons to fall in love with film.

There's a hundred different ways to appreciate the medium, which gives someone like me a hundred different ways to describe it. Maybe more.

You can love a film for its form, for its visuals, for the way it uses space and time. You can love it for its message, that there's a core truth there just itching to be talked about -- something you respond to, something that makes your heart flutter and feel wild. You can love it for its heavy editing, or long, extended takes with no editing, or scenes that creatively cut to form a backwards chronology.

You can love it for its romantic characters that you want to fall in love with, too.

You can love it for the sheer power of image as it drips off the screen into your heart.

We love some movies for the joy they bring -- they make us laugh! We love others for their longing, even their sorrow. Some sad movies touch our soul and cause our eyes to well up with tears, when it has been years since we cried before seeing it. We love others for their maze of dream logic, the way they confuse us and make us wander through the labyrinth designs of our mind. (I'm talking to you, Inception!)

In the next few days I'll once again be seeing, and this time writing about Julie Taymor's Titus. It's a film I love for its visual gravity, a sometimes gruelling and dark picture but nonetheless a perfectly imagined eye myth. I love it, too, for the way it brings the rich words of Shakespeare to life.

When I wrote about 35 rhums, which came alive for me in reading someone else's review, I learned how a small, quiet ensemble film made use of repetition and ellipsis, and the more I considered the approach the more beautiful the structure became.

When I described I Am Love, I was blown away at the way it uses various approaches in cinematography which bring spacing to the different storied sections of the film. I was also riveted by Tilda Swinton's amazing, restrained performance. (All of these reasons and I've barely mentioned acting!)

When I wrote about Vincere I talked about the archival footage that was spliced into the narrative -- old black and white WWI footage flying dead-on into the center of a the story, shaking the film from mere history to a stylized dance.

The symbolic language of cinema affects us physically, mentally, spiritually, socially. It has even been known to change minds and inspire revolution.

The way the following film got to me was through its music. As English essayist and critic Walter Pater noted, "All art aspires to the condition of music." When You're Strange would be a good little doc on a nice little band, if it weren't for the particular music of this particular band, which makes the film, and thus the art, great.

Music moves over us in so many ways. It can soothe, comfort, arouse, bring anger, cause us to rebel at injustice, cause us to rebel at our parents. Music washes over us and brings inspiration, madness, beauty, chaos. Arcade Fire is creating a lot of memorable, loving havoc in my life right now.

When wrapped in the lush confines of celluloid, music makes the possibilities endless.

I've loved The Doors since first hearing Steve Taylor's song, "Jim Morrison's Grave," years ago. Hearing their music today, Taylor rightly points out, is, "like a watch still ticking on a dead man's wrist." It is timeless because it captures the ethos of a particular era. It puts it in a frame, a picture of another time, like Renoir's Le Moulin de la Galette on a gallery wall -- but culturally violent, dark and stained, a picture of escape from cursed ruin.

Hearing The Doors today helps us relate to a harsh moment in American history where all seemed lost, fractured, crippled -- and out of control, too, thanks to rock music, hippie culture, and the youth movement. Studying the band with the narrating help of Johnny Depp, When You're Strange extracts a great deal of archival footage from their five or six short years together. In watching the clips from the time they were made we relate not only to the band, but to sixties insanity as well.

Any time I see a documentary regarding events from, say, 1965-1974, I think to myself, "These people are absolute nutter-butters." I think UFOs and cows tripping over the moon. Lock up each and every person, because the good folk from this era are as gone as Pink Floyd.

Music and its makers pushed at the need for revolution. Were The Doors really a part of that? You don't really think of them immediately in that way. When you think of Jim Morrison you think of a bearded burned out poet, drunk and reciting lyrics about an Oedipal nightmare into a mirror by candlelight. But when you go back through the albums you'll find songs that captured the heart of the need for revolution: "Five to One" and “Unknown Soldier" are the quickest examples that come to mind.

We need a revolution today just like they needed one then. But we are much more rich and apathetic than the kids of the sixties. One might idolize a time like the sixties, thinking, "Yeah, well, at least they did something." But if films like The Most Dangerous Man in America and The U.S. vs. John Lennon and When You're Strange are an indication of what it might look like to actually have a cultural revolution right here and right now -- wow. I can't decide whether all that insanity is a better course of action or not. Do we really want kids shot on college campuses here because they want change there?

There is little doubt that if things went down the way they're shown in When You're Strange, you might as well be out of your mind on acid and let the pretend demons drown out the literal ones. And that is essentially what happened to Jim Morrison. He had to escape it all: his own inflated rock-god ego, the insanity of being a human and being worshipped, greedy men that wanted a hand in his pocket, corrupt politics and institutions, a self-righteous church, the movements, the war, and his Air Force father whom he obviously feared. His way to escape all this was simply to let it all hang out, to push his depravity as far as he could, and to let his mind melt dead in the face of alcohol and drugs.

This film can be loved, even celebrated, for a great rock and roll band and their great music, yes. But it is also an excellent chronology on what and when things went wrong for the band. We see Jim slip into chaos. We see band mates that want to help but are unable to. We see him taunt crowds, enjoy rioting atmospheres, even incite the fans into his own turmoil. Over the years the band went from THE MUSIC to THE SPECTACLE. It is only natural the spectacle would eventually collapse on itself.

The documentary presents events that are portrayed closer to the Oliver Stone biopic than I thought. That is very cool -- I've often wondered how close that stylized film is.

There is no doubt these guys were one of the first great dark bands that blew flower power out the window and sought both reality and escape from reality. They were skeptical of hope, living in the dark, pointing to it everywhere. The dark was reality at that time. The only known escape was to zone out.

It's too bad Morrison had to let the reality of the times completely tear his life apart, leaving him dead at the age of twenty-seven. It's too bad he couldn't really be part of the answer. Too beaten by the world and so enraptured in his insanity, he couldn't recognize that reality changes as we change reality.

Thanks for the music, Jim. Still, I feel for you. For the hard life you lived, for the hard life you brought on yourself. We've still got a piece of you in the legacy of music you left behind. I'm thinking it was a more beautiful contribution than you could even fathom.

May you rest in peace.

There's a hundred different ways to appreciate the medium, which gives someone like me a hundred different ways to describe it. Maybe more.

You can love a film for its form, for its visuals, for the way it uses space and time. You can love it for its message, that there's a core truth there just itching to be talked about -- something you respond to, something that makes your heart flutter and feel wild. You can love it for its heavy editing, or long, extended takes with no editing, or scenes that creatively cut to form a backwards chronology.

You can love it for its romantic characters that you want to fall in love with, too.

You can love it for the sheer power of image as it drips off the screen into your heart.

We love some movies for the joy they bring -- they make us laugh! We love others for their longing, even their sorrow. Some sad movies touch our soul and cause our eyes to well up with tears, when it has been years since we cried before seeing it. We love others for their maze of dream logic, the way they confuse us and make us wander through the labyrinth designs of our mind. (I'm talking to you, Inception!)

In the next few days I'll once again be seeing, and this time writing about Julie Taymor's Titus. It's a film I love for its visual gravity, a sometimes gruelling and dark picture but nonetheless a perfectly imagined eye myth. I love it, too, for the way it brings the rich words of Shakespeare to life.

When I wrote about 35 rhums, which came alive for me in reading someone else's review, I learned how a small, quiet ensemble film made use of repetition and ellipsis, and the more I considered the approach the more beautiful the structure became.

When I described I Am Love, I was blown away at the way it uses various approaches in cinematography which bring spacing to the different storied sections of the film. I was also riveted by Tilda Swinton's amazing, restrained performance. (All of these reasons and I've barely mentioned acting!)

When I wrote about Vincere I talked about the archival footage that was spliced into the narrative -- old black and white WWI footage flying dead-on into the center of a the story, shaking the film from mere history to a stylized dance.

The symbolic language of cinema affects us physically, mentally, spiritually, socially. It has even been known to change minds and inspire revolution.

The way the following film got to me was through its music. As English essayist and critic Walter Pater noted, "All art aspires to the condition of music." When You're Strange would be a good little doc on a nice little band, if it weren't for the particular music of this particular band, which makes the film, and thus the art, great.

Music moves over us in so many ways. It can soothe, comfort, arouse, bring anger, cause us to rebel at injustice, cause us to rebel at our parents. Music washes over us and brings inspiration, madness, beauty, chaos. Arcade Fire is creating a lot of memorable, loving havoc in my life right now.

When wrapped in the lush confines of celluloid, music makes the possibilities endless.

I've loved The Doors since first hearing Steve Taylor's song, "Jim Morrison's Grave," years ago. Hearing their music today, Taylor rightly points out, is, "like a watch still ticking on a dead man's wrist." It is timeless because it captures the ethos of a particular era. It puts it in a frame, a picture of another time, like Renoir's Le Moulin de la Galette on a gallery wall -- but culturally violent, dark and stained, a picture of escape from cursed ruin.

Hearing The Doors today helps us relate to a harsh moment in American history where all seemed lost, fractured, crippled -- and out of control, too, thanks to rock music, hippie culture, and the youth movement. Studying the band with the narrating help of Johnny Depp, When You're Strange extracts a great deal of archival footage from their five or six short years together. In watching the clips from the time they were made we relate not only to the band, but to sixties insanity as well.

Any time I see a documentary regarding events from, say, 1965-1974, I think to myself, "These people are absolute nutter-butters." I think UFOs and cows tripping over the moon. Lock up each and every person, because the good folk from this era are as gone as Pink Floyd.

Music and its makers pushed at the need for revolution. Were The Doors really a part of that? You don't really think of them immediately in that way. When you think of Jim Morrison you think of a bearded burned out poet, drunk and reciting lyrics about an Oedipal nightmare into a mirror by candlelight. But when you go back through the albums you'll find songs that captured the heart of the need for revolution: "Five to One" and “Unknown Soldier" are the quickest examples that come to mind.

We need a revolution today just like they needed one then. But we are much more rich and apathetic than the kids of the sixties. One might idolize a time like the sixties, thinking, "Yeah, well, at least they did something." But if films like The Most Dangerous Man in America and The U.S. vs. John Lennon and When You're Strange are an indication of what it might look like to actually have a cultural revolution right here and right now -- wow. I can't decide whether all that insanity is a better course of action or not. Do we really want kids shot on college campuses here because they want change there?

There is little doubt that if things went down the way they're shown in When You're Strange, you might as well be out of your mind on acid and let the pretend demons drown out the literal ones. And that is essentially what happened to Jim Morrison. He had to escape it all: his own inflated rock-god ego, the insanity of being a human and being worshipped, greedy men that wanted a hand in his pocket, corrupt politics and institutions, a self-righteous church, the movements, the war, and his Air Force father whom he obviously feared. His way to escape all this was simply to let it all hang out, to push his depravity as far as he could, and to let his mind melt dead in the face of alcohol and drugs.

This film can be loved, even celebrated, for a great rock and roll band and their great music, yes. But it is also an excellent chronology on what and when things went wrong for the band. We see Jim slip into chaos. We see band mates that want to help but are unable to. We see him taunt crowds, enjoy rioting atmospheres, even incite the fans into his own turmoil. Over the years the band went from THE MUSIC to THE SPECTACLE. It is only natural the spectacle would eventually collapse on itself.

The documentary presents events that are portrayed closer to the Oliver Stone biopic than I thought. That is very cool -- I've often wondered how close that stylized film is.

There is no doubt these guys were one of the first great dark bands that blew flower power out the window and sought both reality and escape from reality. They were skeptical of hope, living in the dark, pointing to it everywhere. The dark was reality at that time. The only known escape was to zone out.

It's too bad Morrison had to let the reality of the times completely tear his life apart, leaving him dead at the age of twenty-seven. It's too bad he couldn't really be part of the answer. Too beaten by the world and so enraptured in his insanity, he couldn't recognize that reality changes as we change reality.

Thanks for the music, Jim. Still, I feel for you. For the hard life you lived, for the hard life you brought on yourself. We've still got a piece of you in the legacy of music you left behind. I'm thinking it was a more beautiful contribution than you could even fathom.

May you rest in peace.

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

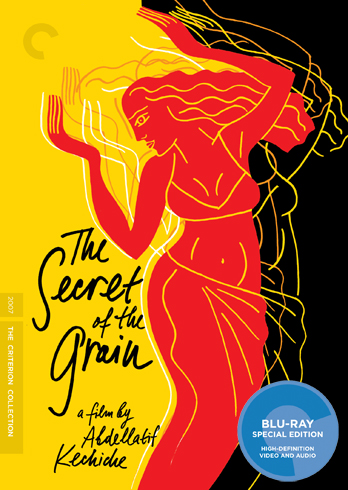

The Secret of the Grain. (2007)

Abdellatif Kechiche

Think about the moments in which a payoff is worth the suspense of a build. The Sixth Sense and Unforgiven are easy examples to cite, but films like Dogville and Ordet are probably more my thing.

What I'm trying to describe are stories in which you hang in there for a period of time -- sometimes not even knowing exactly why you've stuck with it to this point -- and something so wonderful happens in the end that you want to go back and watch it all again just to see if it's as good when you know what's coming.

There is a wonderful payoff in The Secret of the Grain. It is so totally unexpected -- it simply comes out of left field. It is exotic, too -- not necessarily erotic, but a turn-on nonetheless. But even in admitting this much, I would have no problem recommending the film to any reasonable adult. I won't give away anything more than that, other than to stress that it brings a level of fulfilled closure that is rare in cinema these days.

The story is about an old man, Slimane, the generations of his offspring, and the fact that his go-nowhere shipyard job has never provided anything drastic to alter their lives. He wants to do something that will make a difference in the financial futures of his kids, and their kids. He wants to be remembered for actually leaving them something. But now, after years of hard labor, he's still got nothing to give.

So he decides to open a restaurant. On a boat. On an abandoned old wreck of a boat that he's going to have to put a lot of work into and fix up. He has no experience in business or in understanding restaurants. He only knows that his ex-wife's couscous are delicious -- the talk of every family meal. People in his restaurant will return time and again for the couscous. Now in his mid-sixties, Slimane plunges forward into a new phase of life, informing the family, and his ex-wife, he's going to need their help. Bit by bit they reluctantly go along.

He's also going to have to go through a lot of legal red tape to get this idea afloat. His girlfriend's daughter, Rym, barely even college aged, seems to always know how to maneuver the red tape legalities. She gets the permits for zoning laws, the clean kitchen regulations, the location legalities of the boat on the dock, all of that. She begins to appear more and more until we've actually transitioned into a story about a young woman who will go to any length to help her mom's older boyfriend -- and in the end, both of their fates will be sealed by the dedication of the loved ones around them.

The film is shot dogme-style, with handheld cameras and extreme facial close-ups. The cast is a combination of professional and non-professional actors. Some of the scenes are extended so long that it feels the director is searching and searching, and he will prolong the scene until he finds whatever it is he's searching for. It is a long film, and arguments against it are that it is too long and that scenes go on forever. I didn't feel that -- not once. When I saw A Prophet, a similarly lengthy film, I did feel that from about twenty minutes in. Here, relations between the two families -- one that is traditionally North African living in Sète, and the other native to France, are filled with a dividing tension that gives layers in watching them try to realize the old man's dream together. Make no mistake -- it is a racial thing. So we have a story of two families filled with all kinds of prejudices who must work together to get this new restaurant going, and every character gets to bring a unique kind of representation to the film. Like the Corleones in The Godfather, we get a chance to clearly see them all, at least one time each, and each and every one are interesting in their respective scene.

But old man Slimane, the lovely young Rym, and Slimane's son, who is going to bring a form of unalterable destruction through his sex-addictive behavior, are three characters who stand out as clearly as any character I've seen this year. I will not only visit this again soon, I'll remember these characters forever.

And oh -- that final scene! Riveting. Pure genius. And from out of nowhere.

What I'm trying to describe are stories in which you hang in there for a period of time -- sometimes not even knowing exactly why you've stuck with it to this point -- and something so wonderful happens in the end that you want to go back and watch it all again just to see if it's as good when you know what's coming.

There is a wonderful payoff in The Secret of the Grain. It is so totally unexpected -- it simply comes out of left field. It is exotic, too -- not necessarily erotic, but a turn-on nonetheless. But even in admitting this much, I would have no problem recommending the film to any reasonable adult. I won't give away anything more than that, other than to stress that it brings a level of fulfilled closure that is rare in cinema these days.

The story is about an old man, Slimane, the generations of his offspring, and the fact that his go-nowhere shipyard job has never provided anything drastic to alter their lives. He wants to do something that will make a difference in the financial futures of his kids, and their kids. He wants to be remembered for actually leaving them something. But now, after years of hard labor, he's still got nothing to give.

So he decides to open a restaurant. On a boat. On an abandoned old wreck of a boat that he's going to have to put a lot of work into and fix up. He has no experience in business or in understanding restaurants. He only knows that his ex-wife's couscous are delicious -- the talk of every family meal. People in his restaurant will return time and again for the couscous. Now in his mid-sixties, Slimane plunges forward into a new phase of life, informing the family, and his ex-wife, he's going to need their help. Bit by bit they reluctantly go along.

He's also going to have to go through a lot of legal red tape to get this idea afloat. His girlfriend's daughter, Rym, barely even college aged, seems to always know how to maneuver the red tape legalities. She gets the permits for zoning laws, the clean kitchen regulations, the location legalities of the boat on the dock, all of that. She begins to appear more and more until we've actually transitioned into a story about a young woman who will go to any length to help her mom's older boyfriend -- and in the end, both of their fates will be sealed by the dedication of the loved ones around them.

The film is shot dogme-style, with handheld cameras and extreme facial close-ups. The cast is a combination of professional and non-professional actors. Some of the scenes are extended so long that it feels the director is searching and searching, and he will prolong the scene until he finds whatever it is he's searching for. It is a long film, and arguments against it are that it is too long and that scenes go on forever. I didn't feel that -- not once. When I saw A Prophet, a similarly lengthy film, I did feel that from about twenty minutes in. Here, relations between the two families -- one that is traditionally North African living in Sète, and the other native to France, are filled with a dividing tension that gives layers in watching them try to realize the old man's dream together. Make no mistake -- it is a racial thing. So we have a story of two families filled with all kinds of prejudices who must work together to get this new restaurant going, and every character gets to bring a unique kind of representation to the film. Like the Corleones in The Godfather, we get a chance to clearly see them all, at least one time each, and each and every one are interesting in their respective scene.

But old man Slimane, the lovely young Rym, and Slimane's son, who is going to bring a form of unalterable destruction through his sex-addictive behavior, are three characters who stand out as clearly as any character I've seen this year. I will not only visit this again soon, I'll remember these characters forever.

And oh -- that final scene! Riveting. Pure genius. And from out of nowhere.

Saturday, August 14, 2010

R&R Isn't Always Rest & Relaxation

A friend of mine recently suggested I've been watching too much glacial cinema. I responded that it's not all I choose to see, but what I find most interesting to write about. There are too many films stuffed with Too. Much. Stuff., and watching an overstuffed film sometimes feels as busy as the rest of everyday life. Contemplative cinema slows me down. It reminds me of days of quiet reflection, being wrapped up in the majesty of a stirring worship service. Quiet reminds me to breathe, to find a center. It helps me relax and fall into reflection. (And sometimes sleep.)

But it's not all I choose to see, and the following four entries are proof. I've seen each of these in the past few weeks; each is enjoyable in its own right. So it's time to get loud and proud. These are the films of Rock and Roll!

Most people know Cameron Crowe for the famous films he has directed, films like Say Anything, Singles and Jerry Maguire. I would imagine there are quite a few of us in the under-40 crowd that don't know where he got his start. Beginning at the tender age of fifteen in the early to mid-70s, Crowe was a field writer for Rolling Stone magazine. He travelled all over the states with bands like The Allman Brothers and Fleetwood Mac and Led Zepelin. I still can't figure out how a 15 year-old gets a job like this -- I don't think I can figure out how anyone anywhere gets a lollipop job like this! -- but the film, which loosely constructs some of the actual events of Crowe's exciting early years of on-location, even on-tour reporting, suggests he misrepresented his age on the phone to a Rolling Stone editor, ending up on the magazine's payroll, immediately thrust into the lifestyle of rock and roll.

The film stars Patrick Fugit, who came out of nowhere to make himself known as William Miller, Crowe's imaginative retelling of himself as a teenage rock journalist about to break into the big time. Kate Hudson turns in a powerful performance as Penny Lane, a mysterious "band aid" (not groupie!) that is the elusive girl you always dreamed of but wish you hadn't. Zooey Deschanel, Billy Crudup and Philip Seymour Hoffman are all stellar in the cast, too -- in fact, the entire ensemble comes together powerfully in this little film that I overlooked from a decade ago. Great live music, chilling scenes of what it is to desire fame and to hang out with those who become famous, and one stand-out scene of a near death experience turned confessional keep the film as fresh as when it was originally released and well worth a second look today.

Think Oliver Stone's The Doors (in my limited understanding, the best rock biopic), but switch in a coming of age story and a pro band consisting of teenage girls, and you've got an idea of what you might see in The Runaways. With Kristen Stewart playing tough, young and ready-to-rock Joan Jett, Dakota Fanning playing the mysterious, seductively cool lead singer Cherie Currie, and Michael Shannon as their true-to-life outrageously abnormal manager Kim Fowley, the story launches into Rockland like the amps are turned up to eleven. Based on Currie's memoir, "Neon Angel," we follow how Fowley put this chick band together and put them on the road, never coming with them in the process. Coming from torn up homes and a desire to rise above, the girls drilled away at their skills and found a way into talent, and success came knocking on the door.

It works great as a rock biopic, but even better as a story about lost souls on the road trying to find the home that's missing, the family that has eluded them. They are searching, longing for that thing they never had -- and at an age with hormones raging and the desire to find the place that feeds and quenches the fire. Many of the places they find do feed and quench but leave them empty in the process. Lust and power never seem to fulfill on their promises, but we all need to find a sense of family, somehow.

Currie had to move on. Jett stayed at the game and wrote, "I love Rock and Roll," solidifying her home in rock and roll culture.

The DVD commentary is interesting in that Jett hangs out with Fanning and a potty-mouthed Stewart for the conversation as they watch the film. It is worth it just to hear Jett not talk about certain scenes.

The most cheesy of the lot, it still has Philip Seymour Hoffman. I mean -- does any film really need anything more than that? It kind of reminds me of a cross between High Fidelity and School of Rock, if the two were filmed together on a big boat off the coast of Great Britain.

No doubt much license is taken, but the film is based on real events. UK radio only alloted thirty minutes of rock and roll running time per day in the mid-sixties. Large boats running pirate DJs threw anchor off the coast, where they couldn't be arrested for broadcasting on British soil. They cranked up the tunes, firing signals to every land-locked citizen in need of rocking out. According to the government at the time, they were guilty of corrupting the youth -- and probably quite a few elders, too.

It is a fun film, but a little too silly except for its historic subject matter. The only thing grounded in reality is what I've already described. Otherwise you can take the idea and add really anything you want, from all the pointless sex on the boat, some of which may have happened but it is mainly shown in its glorification, to the behind the scenes government drama to shut these boats down, to the dramatic rescue of the sinking boat that we've been following -- a rescue which shows government neglect in hope of the death of the floating DJs, and British youth coming to the rescue in what are probably the boats of their parents. Yeah, don't think I can believe all that.

And its idea that rock and roll is going to save the planet is also like having a carrot cake for your birthday party. But like I said, it is a fun film, blending the borders of music and morality, showing perhaps a bit of hypocrisy on both sides of the question, and enjoying itself in the comedic way it makes its point. In my thinking it is good to see mindless oppression confronted -- Pirate Radio is a relatively good example of this. (And the good guys win.)

A reality film created from the recordings of Metallica's eighth studio album, "St. Anger," an album which took over two years of in-band feuding and countless therapy sessions to create, the doc almost got me to actually buy the CD. (I've never bought a Metallica CD. I'm still thinking about this one.) It is a decent film, albeit a bit long. But watching members of the band visiting the sweater-wearing therapist make you think twice about the great life of being a rock star.

Joe Berlinger directed Metallica: Some Kind of Monster a few years before he flew to Ecuador and filmed Crude. Berlinger seems to get better and better at documentary filmmaking. Let's hope the recent lawsuit from Chevron doesn't stop him from even higher heights.

There is no doubt the film changes the way I see the band. They've taken some of their mystery and anger away and let us see a side of their reality, their humanity. It's great to see the rock stars let down their guard and show us how similar they are to the rest of us. God bless the band as they continue to work things out.

But it's not all I choose to see, and the following four entries are proof. I've seen each of these in the past few weeks; each is enjoyable in its own right. So it's time to get loud and proud. These are the films of Rock and Roll!

Almost Famous. (2000) Cameron Crowe

Most people know Cameron Crowe for the famous films he has directed, films like Say Anything, Singles and Jerry Maguire. I would imagine there are quite a few of us in the under-40 crowd that don't know where he got his start. Beginning at the tender age of fifteen in the early to mid-70s, Crowe was a field writer for Rolling Stone magazine. He travelled all over the states with bands like The Allman Brothers and Fleetwood Mac and Led Zepelin. I still can't figure out how a 15 year-old gets a job like this -- I don't think I can figure out how anyone anywhere gets a lollipop job like this! -- but the film, which loosely constructs some of the actual events of Crowe's exciting early years of on-location, even on-tour reporting, suggests he misrepresented his age on the phone to a Rolling Stone editor, ending up on the magazine's payroll, immediately thrust into the lifestyle of rock and roll.

The film stars Patrick Fugit, who came out of nowhere to make himself known as William Miller, Crowe's imaginative retelling of himself as a teenage rock journalist about to break into the big time. Kate Hudson turns in a powerful performance as Penny Lane, a mysterious "band aid" (not groupie!) that is the elusive girl you always dreamed of but wish you hadn't. Zooey Deschanel, Billy Crudup and Philip Seymour Hoffman are all stellar in the cast, too -- in fact, the entire ensemble comes together powerfully in this little film that I overlooked from a decade ago. Great live music, chilling scenes of what it is to desire fame and to hang out with those who become famous, and one stand-out scene of a near death experience turned confessional keep the film as fresh as when it was originally released and well worth a second look today.

The Runaways. (2010) Floria Sigismondi

Think Oliver Stone's The Doors (in my limited understanding, the best rock biopic), but switch in a coming of age story and a pro band consisting of teenage girls, and you've got an idea of what you might see in The Runaways. With Kristen Stewart playing tough, young and ready-to-rock Joan Jett, Dakota Fanning playing the mysterious, seductively cool lead singer Cherie Currie, and Michael Shannon as their true-to-life outrageously abnormal manager Kim Fowley, the story launches into Rockland like the amps are turned up to eleven. Based on Currie's memoir, "Neon Angel," we follow how Fowley put this chick band together and put them on the road, never coming with them in the process. Coming from torn up homes and a desire to rise above, the girls drilled away at their skills and found a way into talent, and success came knocking on the door.

It works great as a rock biopic, but even better as a story about lost souls on the road trying to find the home that's missing, the family that has eluded them. They are searching, longing for that thing they never had -- and at an age with hormones raging and the desire to find the place that feeds and quenches the fire. Many of the places they find do feed and quench but leave them empty in the process. Lust and power never seem to fulfill on their promises, but we all need to find a sense of family, somehow.

Currie had to move on. Jett stayed at the game and wrote, "I love Rock and Roll," solidifying her home in rock and roll culture.

The DVD commentary is interesting in that Jett hangs out with Fanning and a potty-mouthed Stewart for the conversation as they watch the film. It is worth it just to hear Jett not talk about certain scenes.

Pirate Radio. (2009) Richard Curtis

The most cheesy of the lot, it still has Philip Seymour Hoffman. I mean -- does any film really need anything more than that? It kind of reminds me of a cross between High Fidelity and School of Rock, if the two were filmed together on a big boat off the coast of Great Britain.

No doubt much license is taken, but the film is based on real events. UK radio only alloted thirty minutes of rock and roll running time per day in the mid-sixties. Large boats running pirate DJs threw anchor off the coast, where they couldn't be arrested for broadcasting on British soil. They cranked up the tunes, firing signals to every land-locked citizen in need of rocking out. According to the government at the time, they were guilty of corrupting the youth -- and probably quite a few elders, too.

It is a fun film, but a little too silly except for its historic subject matter. The only thing grounded in reality is what I've already described. Otherwise you can take the idea and add really anything you want, from all the pointless sex on the boat, some of which may have happened but it is mainly shown in its glorification, to the behind the scenes government drama to shut these boats down, to the dramatic rescue of the sinking boat that we've been following -- a rescue which shows government neglect in hope of the death of the floating DJs, and British youth coming to the rescue in what are probably the boats of their parents. Yeah, don't think I can believe all that.

And its idea that rock and roll is going to save the planet is also like having a carrot cake for your birthday party. But like I said, it is a fun film, blending the borders of music and morality, showing perhaps a bit of hypocrisy on both sides of the question, and enjoying itself in the comedic way it makes its point. In my thinking it is good to see mindless oppression confronted -- Pirate Radio is a relatively good example of this. (And the good guys win.)

Metallica: Some Kind of Monster. (2004) Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky

A reality film created from the recordings of Metallica's eighth studio album, "St. Anger," an album which took over two years of in-band feuding and countless therapy sessions to create, the doc almost got me to actually buy the CD. (I've never bought a Metallica CD. I'm still thinking about this one.) It is a decent film, albeit a bit long. But watching members of the band visiting the sweater-wearing therapist make you think twice about the great life of being a rock star.

Joe Berlinger directed Metallica: Some Kind of Monster a few years before he flew to Ecuador and filmed Crude. Berlinger seems to get better and better at documentary filmmaking. Let's hope the recent lawsuit from Chevron doesn't stop him from even higher heights.

There is no doubt the film changes the way I see the band. They've taken some of their mystery and anger away and let us see a side of their reality, their humanity. It's great to see the rock stars let down their guard and show us how similar they are to the rest of us. God bless the band as they continue to work things out.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

R.I.P., Bruno S. (1932 - 2010)

Mubi has an article posted Here.

It is interesting timing that I just watched and wrote about his two well-known films from the seventies. He was a fascinating character, so odd, so out there. I guess if you grew up the way he grew up, you'd have lived an odd life, too.

Here are my reactions to Stroszek and The Enigma of Kasper Hauser.

May you rest in peace, Bruno.

Monday, August 9, 2010

Cold Souls. (2009) Sophie Barthes

I want to call this a genre film, but I don't know what the genre is.

The genre, for me anyway, goes back to the writings of Charlie Kaufman as brought to life by directors Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry. Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind launched the movement, which later gave way for the ever-imaginative The Science of Sleep, and the utterly depressing Synecdoche, New York (which, in all its depression, I still quite admire).

It seems that international directors got involved in the genre, too -- for instance with Christoffer Boe's Reconstruction and Allegro, and Emmanuel Carrère's La moustache.

It's a movement of films based on lost identity, swapped memory, soul searching and human longing. I'm tempted to call it "Pseudo-contemplative with a wry comedic twist," but the word "comedic" can be misleading. I'm also tempted to call it simply "Cerebral lite" or "Fun-pop-Psychological."

I don't know what to call it, but it's a genre I love.

Cold Souls fits in pretty well with the rest of these imaginative stories.

Like John Malkovich in Being John Malkovich, Paul Giamatti turns in a wonderful performance as himself. Or maybe it really isn't himself, since he's had his soul extracted and tried out someone else's. It's great fun when these actors play themselves but when there's a loophole that makes it not really them.

As with the other films I've mentioned, where identity, memory, and reality of the mind is either distorted, infected or has simply gone astray, when you trade in your soul and try on another it only leaves you soul-sick.

If there's any message here it is simply loving yourself for who you are, learning to live at peace in your own skin, attempting to work on yourself and the parts you don't like. That working on yourself and finding peace in your soul is better than envying anyone else.

It's a great message, but the movie is even better when you don't think too hard about it. And you don't have to. It's a film filled with paradoxes and contradictions (if you are carrying another peron's soul and they die, does the soul stay in you or does it die, too?), but it's fun and smart, light and easy, and worth renting for another perfect Giamatti performance.

Filmwell has a wonderful, more in-depth analysis of Cold Souls.

The genre, for me anyway, goes back to the writings of Charlie Kaufman as brought to life by directors Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry. Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind launched the movement, which later gave way for the ever-imaginative The Science of Sleep, and the utterly depressing Synecdoche, New York (which, in all its depression, I still quite admire).

It seems that international directors got involved in the genre, too -- for instance with Christoffer Boe's Reconstruction and Allegro, and Emmanuel Carrère's La moustache.

It's a movement of films based on lost identity, swapped memory, soul searching and human longing. I'm tempted to call it "Pseudo-contemplative with a wry comedic twist," but the word "comedic" can be misleading. I'm also tempted to call it simply "Cerebral lite" or "Fun-pop-Psychological."

I don't know what to call it, but it's a genre I love.

Cold Souls fits in pretty well with the rest of these imaginative stories.

Like John Malkovich in Being John Malkovich, Paul Giamatti turns in a wonderful performance as himself. Or maybe it really isn't himself, since he's had his soul extracted and tried out someone else's. It's great fun when these actors play themselves but when there's a loophole that makes it not really them.

As with the other films I've mentioned, where identity, memory, and reality of the mind is either distorted, infected or has simply gone astray, when you trade in your soul and try on another it only leaves you soul-sick.

If there's any message here it is simply loving yourself for who you are, learning to live at peace in your own skin, attempting to work on yourself and the parts you don't like. That working on yourself and finding peace in your soul is better than envying anyone else.

It's a great message, but the movie is even better when you don't think too hard about it. And you don't have to. It's a film filled with paradoxes and contradictions (if you are carrying another peron's soul and they die, does the soul stay in you or does it die, too?), but it's fun and smart, light and easy, and worth renting for another perfect Giamatti performance.

Filmwell has a wonderful, more in-depth analysis of Cold Souls.

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Sweetgrass. (2010)

Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor

This is a movie about the nature of sheep and the nature of the Montana mountain men who watch over them, guiding them along. "We all like sheep have gone astray..."

The best comparison I can think back to when considering Sweetgrass and its cast of sometimes docile, often willful sheep, and the sheepherders that put their lives on the line for them, is the 2003 nomadic Mongolian family film, The Story of the Weeping Camel. No, there is no messianic sheep to be found in Sweetgrass. But the film's lack of narration to cover over long silences, its similar pacing throughout, and quiet moments of genuine reflection on creation categorize the two similarly.

And that's a good thing.

Some reports around the web call Sweetgrass overly long and "boring." It would seem the bulk of these complaints come from the sixteen-and-under demographic. I have to admit I thought it would be quite fun to rant and rave about an hour and forty minutes of sheep -- there's nothing here but wandering, dirty, flea-ridden sheep! -- but the film I anticipated didn't turn out to be the one I watched. Yes, you can refer to this as a "glacial film", and with its lack of dialogue there is no doubt it has challenging moments. But the lack of dialogue here is better than some films that have too much. I'd rather watch sheep for an hour and forty minutes, which say much with no words, than spend another second with this weekend's horrible box office winner, The Other Guys, in which many people say too much for an excruciating hour and forty minutes -- none of it worth consideration or future remembrance.

"Glacial," it would seem, is a relative term.

Watching these creatures eat, get together in a flock and get into unified motion like cells in the blood or Sentinels in The Matrix, watching the birth of a little one and a mother who fights the nursing process, watching their gentle understanding during the shearing process (it's like they wanted that heavy insulation removed and trusted the sheepherders to get the job done), and the stubborn, ornery ways in which they wander away in group-think is like watching aliens on a faraway planet -- a non-understanding alien race capable of intelligence, but willing slaves to a planet relative, having their needs taken care of, trading wool for care. The human and sheep are in a symbiotic relationship, a commensal relationship which brings protection to an unprotected creature and benefits to the one willing to protect.

The sheepherders -- who are more like cowboys -- take a flock of 3000 on a 150 mile journey through mountain terrain. Their horses and dogs falter. Their sheep wander over canyons. Wolverines and bears are a constant night time threat. They get depressed, angry at the mountains, scared they won't make the trip. They curse and pray at the same time. One calls home to mom in a near cry -- his knee is hurt, and he's got a long way to go to complete the journey ahead.

A husband and wife team spent two years capturing the sheep on the journey. What they've caught is a dazzling visual feast. There is no CGI -- no talking sheep or dancing Montana bears to make you laugh and clock in early. This is film, the same way the medium began in the early part of last century. There's something wonderful about going back to nature, just as there is something wonderful about going back to film -- no computers, no tricks, no gimmickery.

Authenticity is the key to loving Sweetgrass.

The best comparison I can think back to when considering Sweetgrass and its cast of sometimes docile, often willful sheep, and the sheepherders that put their lives on the line for them, is the 2003 nomadic Mongolian family film, The Story of the Weeping Camel. No, there is no messianic sheep to be found in Sweetgrass. But the film's lack of narration to cover over long silences, its similar pacing throughout, and quiet moments of genuine reflection on creation categorize the two similarly.

And that's a good thing.

Some reports around the web call Sweetgrass overly long and "boring." It would seem the bulk of these complaints come from the sixteen-and-under demographic. I have to admit I thought it would be quite fun to rant and rave about an hour and forty minutes of sheep -- there's nothing here but wandering, dirty, flea-ridden sheep! -- but the film I anticipated didn't turn out to be the one I watched. Yes, you can refer to this as a "glacial film", and with its lack of dialogue there is no doubt it has challenging moments. But the lack of dialogue here is better than some films that have too much. I'd rather watch sheep for an hour and forty minutes, which say much with no words, than spend another second with this weekend's horrible box office winner, The Other Guys, in which many people say too much for an excruciating hour and forty minutes -- none of it worth consideration or future remembrance.

"Glacial," it would seem, is a relative term.

Watching these creatures eat, get together in a flock and get into unified motion like cells in the blood or Sentinels in The Matrix, watching the birth of a little one and a mother who fights the nursing process, watching their gentle understanding during the shearing process (it's like they wanted that heavy insulation removed and trusted the sheepherders to get the job done), and the stubborn, ornery ways in which they wander away in group-think is like watching aliens on a faraway planet -- a non-understanding alien race capable of intelligence, but willing slaves to a planet relative, having their needs taken care of, trading wool for care. The human and sheep are in a symbiotic relationship, a commensal relationship which brings protection to an unprotected creature and benefits to the one willing to protect.

The sheepherders -- who are more like cowboys -- take a flock of 3000 on a 150 mile journey through mountain terrain. Their horses and dogs falter. Their sheep wander over canyons. Wolverines and bears are a constant night time threat. They get depressed, angry at the mountains, scared they won't make the trip. They curse and pray at the same time. One calls home to mom in a near cry -- his knee is hurt, and he's got a long way to go to complete the journey ahead.

A husband and wife team spent two years capturing the sheep on the journey. What they've caught is a dazzling visual feast. There is no CGI -- no talking sheep or dancing Montana bears to make you laugh and clock in early. This is film, the same way the medium began in the early part of last century. There's something wonderful about going back to nature, just as there is something wonderful about going back to film -- no computers, no tricks, no gimmickery.

Authenticity is the key to loving Sweetgrass.

Saturday, August 7, 2010

Vincere. (2010) Marco Bellocchio