Crimes and Misdemeanors. (1989) Woody Allen

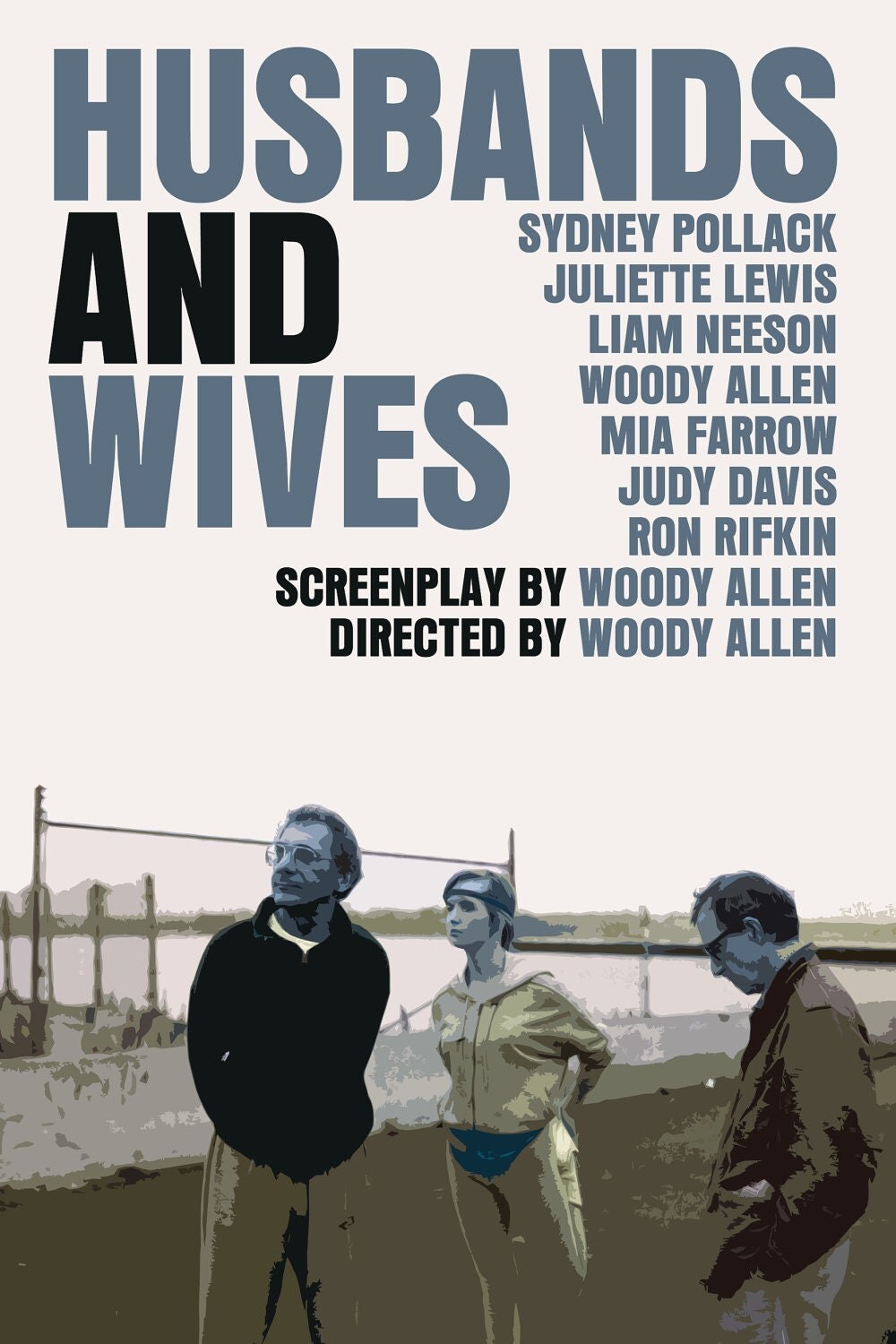

Husbands and Wives. (1992) Woody Allen

I've been falling drastically behind in my blogging attempts at keeping up with the A&F Marriage Nominations, but here are two I've caught over the last couple weeks that completely took me by surprise.

Why surprise? Probably because I don't consider myself the biggest fan of Woody Allen. I've got nothing against him, in fact I've enjoyed quite a few of his films over the years (Midnight in Paris even crept into the #10 spot on last year's Top Ten Films) -- but somewhere in the back of my mind I've labeled Allen-directed films as "romcom," and it's a genre I typically try to avoid, no matter how well-made.

It's a shame actually, because looking over his list of films, at least five have left a positive imprint in the back of my mind. So I guess my enjoyment of the two films here should really be little surprise at all.

Crimes and Misdemeanors, a film which sits at #79 on the A&F Top 100, sets its eye firmly on ethics, as it deals with the ramifications of both adultery and murder. It questions whether certain sins are tiered as higher or lower, whether sin and morality are man-made constructs which keep a peaceful code and hold things together -- ingrained in our psyche to keep humanity from tearing ourselves apart -- or whether these codes of conduct are derived from a larger plan, coming from a God (here represented from Jewish tradition), who has rules for mankind lest we be thrown into the bowels of hell.

The film follows parallel story lines, both intricately weaved into this theme. Allen's character, Cliff, is a documentary filmmaker, compromising his principles by taking a better paying job creating a TV-style documentary on his more successful film-making brother-in-law (played by the ever-exuberant Alan Alda). Cliff would rather be taking a new mistress and working with her on the documentary he had planned, which centers on an aging theologian and Old Testament philosopher who is a little out of touch with the ordinary citizen. It's a safe bet that nothing here is going to work for Cliff -- that he'll be let down in numerous (and lightly comedic) ways before his part in the story comes to an end.

The other story follows Judah (Martin Landau) as an opthamologist in serious trouble. An affair he has had for the previous two years has spun out of control, his mistress threatening to approach his wife with the details. Judah's brother, a man with a sordid past and crimes too many to count, recommends the easiest way to take care of the problem: get rid of this mistress, quickly, and permanently. Later, Judah has some guests over at the house when he receives a phone call from his brother. The deed is done. We watch as his betraying heart grapples with the guilt. We watch as he grieves, but gets away with it.

Two ghostly scenes I will always remember from Crimes and Misdemeanors. Both come out of nowhere, and both feel like visits from Jacob Marley to a quivering Ebeneezer Scrooge. Landau's Judah has a dreamy drop-in visit from his rabbi, who is also a patient and friend. The dreamy conversation they have describes the implications of Judah's potential crime, drawn up so tightly as to invade the very light in the room. Later, on a simple spontaneous visit to the house he grew up in, Judah ends up in conversation with his entire extended family (around a long rectangular table in an imagined dinner together) on fixed Universal morality, with the suggestion that whether there's a God or not, murder will "out" itself.

The film ends at a cocktail party where the two finally meet. Judah gives Cliff an idea for a film, and begins to talk, in detail, about the events of his crime as it has played out. The two sit and sip liquor: the one that seemingly gets away with everything, and the more innocent one who will be the loser no matter what the future holds. It is a strange combination, these two and this conversation, perfectly placed at the story's end as a climactic dialogue of sorts. How fitting that a conversation, the stuff where Allen excels, would make for a perfectly climactic ending to a movie based less on plot and more on underlying motivations.

This is a witty film, full of interesting questions about sin and the possibility that there might not even be such a thing if there is no higher power. It reads like a story, in fact that is what it is -- but it feels like a paper, a treatise of sorts, or an essay for a college philosophy class. The fact that it's still so entertaining while weighing all these heavy thoughts speaks to the level of talent in Allen's writing.

Husbands and Wives is a little different in the way it formally presents itself. The story is told in present tense, and begins with a couples get-together in which Jack and Sally (Sydney Pollack and Judy Davis) meet at the apartment of Gabe and Judy (Allen and Mia Farrow, acting at this point in their last year of marriage), ready to go to dinner as the four sometimes do -- but on this night Jack and Sally begin with a casual announcement of their separation, the shocking news of which crushes Judy. The couples proceed with their dinner plans, trying to make the best of their night, but the film takes us by surprise when it suddenly cuts to Judy, breaking the fourth wall in a documentary interview, trying to piece together why she was so upset.

From here, we never really know what we're watching. Is it a story, or a documentary, or a documentary crew following the characters in present tense reality? The answer to this question turns out to be, "Yes."

This isn't the only thing that threw me for a bit of a loop in watching Husbands and Wives: the nature of the handheld camera work, the hard edits which establish shifts in emotional response, the zoom of the lens itself which functions in much the same way, and back and forth weaving between straight narrative and documentary interruption are all a bit "edgy," in my opinion, for the time the film was made. Created in 1992, it feels like it must have been a bit ahead of the curve when it came out. This is smart story telling, not happy with taking its characters simply from Point A to Point B, but throwing in a few indentations and formal (artsy) ticks along the way.

The dialogue, again, is top notch. Like the presentation itself, and the indentations I've noted, Woody Allen dialogue is never used as a plot device to simply propel characters in a narrative arc; rather, the way these characters speak to each other springs from the kinds of real conversations people in this setting might actually have. The tempo is lively (one has to sometimes wonder whether anyone is allowed to take time to think before they speak), but there is always something deeper going on than a simple convo that leads to another scene.

Like Crimes and Misdemeanors, Husbands and Wives will also end ironically with the director being the most unfulfilled of the whole cast. One has to wonder if this was a period in Allen's life when in two films he comedically expressed some inner turmoil.

Both films are worth seeking out, and will be getting very high rankings in the vote I'll be taking part in this weekend. As far as films for the marriage category, they'll both be getting a solid 4/5 from me. I've been happy to be introduced to these older gems, and I'd love to seek out other older films from Woody Allen.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I like to respond to comments. If you keep it relatively clean and respectful, and use your name or any name outside of "Anonymous," I will be much more apt to respond. Spam or stupidity is mine to delete at will. Thanks.