Ordet. (1955) Carl Theodor Dreyer

The list used to be called the "Arts and Faith Top 100 Most Spiritually Significant Films." This year, after much lobbying from a few of us (yours truly, included) we've whittled it down to be called, simply, "The Arts and Faith Top 100 Films." It's a sufficient explanation, but taking out that tiny word "spiritual" probably threw quite a few of us off in the voting process. To look at a film in light of its so-called "spirituality" is indeed different than looking at it purely from an "arts and faith" standpoint. The list has changed quite a bit over the years, and this recent iteration is no different -- but there are still 40 films that have made it on all four versions so far.

Our hosts at IMAGE will be creating a main page for the t100 (as I like to refer to it), and 100 separate pages -- one page for each of the films, and we'll be writing a blurb for each regarding why we chose it, of our love for the work and the reasoning behind its inclusion. This year we had 44 voters spanning some of the top Christian critics in both print and on the net, to your average a&f cinephile like myself. Votes were gathered from several continents and results range from films in the 1920s through present day.

Here are the results, and again, I can't stress how happy I am:

1. Ordet, 1955, Carl Theodor Dreyer

2. The Decalogue ("Dekalog"), 1987, Krzysztof Kieslowski

3. Babette’s Feast, 1987, Gabriel Axel

4. The Passion of Joan of Arc, 1928 Carl Theodor Dreyer

5. The Son, ("Le Fils"), 2002, Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne

6. Au Hasard Balthazar, 1966, Robert Bresson

7. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, 1927, F.W. Murnau

8. Andrei Rublev, 1969, Andrei Tarkovsky

9. Early Summer ("Bakushû"), 1951, Yasujiro Ozu

10. The Gospel According to Matthew, 1964, Pier Paolo Pasolini

11. The Diary of a Country Priest, 1951, Robert Bresson

12. Wings of Desire, 1987, Wim Wenders

13. The Seventh Seal, 1957, Ingmar Bergman

14. Ikiru, 1952, Akira Kurosawa

15. Three Colors Trilogy, 1993, 1994, 1994, Kryzysztof Kieslowski

16. The Mirror, 1975, Andrei Tarkovsky

17. Apu Trilogy (Pather Panchali, Aparajito, Apu Sansar), 1955/56/59, Satyajit Ray

18. Floating Weeds, 1959, Yasujiro Ozu

19. Munyurangabo, 2007, Lee Isaac Chung

20. The Burmese Harp, 1956, Kon Ichikawa

21. Tokyo Story, 1953, Yasujiro Ozu

22. A Serious Man, 2009, Ethan and Joel Coen

23. My Night at Maud's, 1969, Eric Rohmer

24. Into Great Silence, 2005, Philip Gröning

25. Nostalghia, 1983, Andrei Tarkovsky

26. Still Life, 2006, Zhang Ke Jia

27. L'Enfant, 2005, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne

28. The Bicycle Thief, 1948, Vittorio De Sica

29. A Man Escaped, 1956, Robert Bresson

30. Stalker, 1979, Andrei Tarkovsky

31. A Man for All Seasons, 1966, Fred Zinnemann

32. The Apostle, 1997, Robert Duvall

33. The Island, ("Ostrov"), 2006, Pavel Lungin

34. Close-Up ("Nema-ye Nazdik"), 1990, Abbas Kiarostami

35. Wild Strawberries, 1957, Ingmar Bergman

36. Days of Heaven, 1978, Terrence Malick

37. Playtime, 1967, Jacques Tati

38. Winter Light, 1963, Ingmar Bergman

39. Through a Glass Darkly ("Såsom i en spegel"), 1961, Ingmar Bergman

40. The House is Black, (Khaneh siah ast), 1964, Forugh Farrokhzad

41. Summer / The Green Ray ("Le Rayon vert"), 1986, Eric Rohmer

42. Day of Wrath (“Vredens dag”), 1943, Carl Theodor Dreyer

43. Silent Light, 2007, Carlos Reygadas

44. La Promesse, Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne

45. It's a Wonderful Life, 1946, Frank Capra

46. M, 1931, Fritz Lang

47. Late Spring ("Banshun"), 1972, Yasujiro Osu

48. Killer of Sheep, 1977, Charles Burnett

49. Solaris, 1972, Andrei Tarkovsky

50. The Cyclist, ("Bicycleran"), 1987, Mohsen Makhmalbaf

51. The Spirit of the Beehive, ("El espíritu de la colmena"), 1973, Víctor Erice

52. Cries and Whispers, 1973, Ingmar Bergman

53. My Life to Live, 1962, Jean-Luc Godard

54. The Straight Story, 1999, David Lynch

55. Flowers of St. Francis, 1950, Roberto Rossellini

56. Ponette, 1996, Jacques Doillon

57. The Wind Will Carry Us, 1999, Abbas Kiarostami

58. Magnolia, 1999, Paul Thomas Anderson

59. Faust, 1926, F.W. Murnau

60. Fanny and Alexander, 1982, Ingmar Bergman

61. Paris, Texas, 1984, Wim Wenders

62. A Moment of Innocence, 1997, Mohsen Makhmalbaf

63. The Trial of Joan of Arc, 1962, Robert Bresson

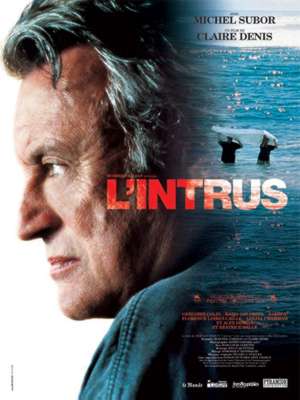

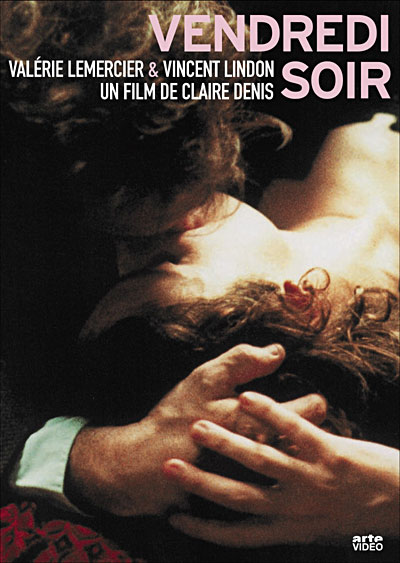

64. Beau travail, 1999, Claire Denis

65. After Life, 1999, Hirokazu Koreeda

66. By Brakhage: An Anthology, 2003, Stan Brakhage

67. Lorna's Silence, 2008, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne

68. 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, 2007, Cristian Mungiu

69. Chariots of Fire, 1982, Hugh Hudson

70. Derzu Uzala, 1975, Akira Kurosawa

71. An Autumn Afternoon, 1962, Yasujiro Ozu

72. Heartbeat Detector, 2007, Nicolas Klotz

73. Tender Mercies, 1983, Bruce Beresford

74. Summer Hours, 2008, Olivier Assayas

75. Rashômon, 1950, Akira Kurosawa

76. Becket, 1964, Peter Glenville

77. Black Narcissus, 1947, Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

78. Eureka, 2000, Shinji Aoyama

79. Meshes in the Afternoon, 1943, Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid

80. Open City ("Roma, citta apera"), 1945, Roberto Rossellini

81. Syndromes and a Century, 2006, Apichatpong Weerasethakul

82. Rosetta, 1999, Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne

83. Yi Yi: A One and a Two, 2000, Edward Yang

84. Pickpocket, 1959, Robert Bresson

85. Punch-Drunk Love, 2002, Paul Thomas Anderson

86. Offret ("The Sacrifice"), 1986, Andrei Tarkovsky

87. Stroszek, 1977, Werner Herzog

88. Jesus of Montreal, 1989, Denys Arcand

89. Ushpizin, 2004, Giddi Dar

90. Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher, 2005, David Di Sabatino

91. Au Revoir, Les Enfants, 1987, Louis Malle

92. Son of Man, 2006, Mark Dornford-May

93. The Virgin Spring, 1960, Ingmar Bergman

94. In Praise of Love, 2001, Jean-Luc Godard

95. Crimes and Misdemeanors, 1989, Woody Allen

96. The New World, 2005, Terrence Malick

97. M. Hulot's Holiday, 1953, Jacques Tati

98. The Return, 2003, Andrei Zvyagintsev

99. Breaking the Waves, 1996, Lars von Trier

100. Song of Bernadette, 1943, Henry King

As per usual after the vote, I have about 40 films to catch up on. I can't wait to get in on the discussion. I'm sure I'll be keeping this little Filmsweep up to date on all the action, as well.

Oh -- and how nice to see both Brakhage and seven Bergmans represented this time around! I am stoked about that. :) And for the first time, all five of the distributed Dardennes films are on the list. I am delighted, I really am about to blow up with excitement! (Yes, I really am that much of a film nerd!)

You are always invited to join the forum at A&F. You can stop by and introduce yourself Here, or just jump into the learning and/or debate & discussion, whenever you think the timing feels right.

See you there.