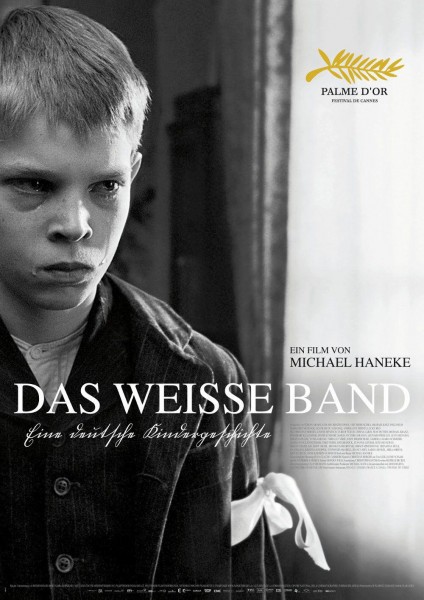

The 2009 Cannes Palme d'Or went to one of my favorite directors and his latest work, The White Ribbon. I was able to catch all of its luscious black and white splendor on a giant Landmark screen opening night in Chicago.

Like many of my favorite films, it's not a story that you discuss in terms of "like" or "dislike". I'm still coming to terms with my own feelings on it. But I do know this -- it's a Haneke film. For a great many years he's been known for agitating his audiences in both wonderful and aggravating ways. I mean, do you really remember Michael Haneke? At one point he had the

But as of late Haneke has been on a monster of a roll. He's growing older and growing up, growing wiser in how to fully engage an audience. He knows exactly which buttons to push, and when to push them. It's as if he flipped the power switch on high and his train won't be derailed.

This decade alone he's softened his well-known bad boy stance and cranked out four serious marvels discussed ad nauseam by dedicated cinephiles around the globe. Of those four, he's probably best known for La pianiste and Caché, which rocketed audiences with the unexpected sights and sounds of sexual and voyeuristic psychology. But it was the interlocking symbols of Code Unknown, and the dreamy apocalyptic nightmare of Time of the Wolf that had me forever hooked on Haneke. Three of these works I also saw on the big screen -- there's not a better way to squeeze light into a space.

We know what we're getting into when we stumble into Haneke film. It's never going to be an easy experience. The mood won't be light by any means. By the time one makes it to the scrolling end credits, you might be stuck in your seat, clawing the armrest. It's not horror, it's humanity, which is sometimes horrifying. It's not terror, it's trauma, and it happens every day.

The White Ribbon, then, is a pre-WWI creeping of sadness unveiled. I'm not persuaded Haneke's point is sadness for sadness' sake, nonetheless it accompanies the lush images like a conjoined twin.

The year is 1913. A village in Germany is subjected to a series of heinous, violent incidents. People are injured or beaten in the town. A note is left at one of the scenes of a grissly crime. Propelled by sweet-looking, uncommonly quiet children, their perfect doe-eyed Arian looks seize us: Are these kids the same adults who will in twenty more years instigate the atrocities of world war horror? Are the children as innocent as they look, even at this tender young impressionable age? Has something affected them already that's determined their destiny?

You can't suppose that the village crimes are committed by these pure kids, can you?

The children are constantly monitored, but they can gather at the edge of town to unwind. When under surveillance, either by the Church or the State, they are puritain moralists, just like mommy and daddy and the teacher and preacher too.

Unfortunately mommy and daddy and the rest of the adults aren't as moral as their influence suggests. When they punish the kids and make them wear a white ribbon (representing the quest for a moral life), the kids see right through all the falsity into the dark secrets hidden in the cracks of every home. A tension is built, the crimes continue, and the kids fall constantly into trouble, but never for the village crimes. This ordeal builds to an unforgettable climax, one that is very reflective of the times (then and now).

I don't understand all the intentions of Al-Qaeda or the Taliban. I know that somewhere along the line, they feel we've done them wrong, and that our entire country should pay for the mistakes in our government. I don't want to say that I have empathy for them because honestly I don't know if I do. It's a situation I don't fully understand. I'm not one to typically spout off about politics that I just don't get.

Terrorism in general is on display in The White Ribbon, if indeed the children are behind the community crimes. And right here, in this context, I think we can understand it. Terror is what's left when you honestly feel there's no other play.

The moralizing system that the adults grind into the kids is closely akin to that of other black and white films like Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc, or more likely, a film I recently wrote about Here, Day of Wrath. When religious and political oppression is lorded over you, when you really have no choice but to continue on -- when you have no voice and no way of electing better representation, hopelessness and fatalism reign.

The children have no chance to speak for themselves. If they really did speak for themselves, if their thoughts for one second were ever made known, the system would crash down like a ton of bricks on their backs, effectively burying them alive. It would totally destroy whatever is left in them that's not already dead.

When you are beaten down and offered no way to live other than what your oppressor says is right, and your will is beyond saving or hope, your options are less and your desire to live diminished. Of course, there's the option of suicide. There's also insanity and escape. And many of the adults' responses to the village oppression goes there. But there's also the option of responding, attacking, striking at the root without naming yourself. We're never certain who the attacker is, but it's someone who has realized the need to strike back.

It may sound insane to suggest that guerilla tactics be applauded among children. I would never suggest this to my own kids! But if my child were daily beaten up at the playground, would I continue to have him or her pray for God to intervene, or at a certain point would I teach how a fist is made? Maybe God's will is sometimes found in the fist.

I'm not saying that if it was the children then Haneke is right. What I'm saying, and I don't think this spoils anything because the point is not about the plot (and besides, you begin to suspect the kids immediately) -- is that if it is the children, Haneke might be right, and like the options I recently talked about in 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, sometimes there is only the greater right of wrong.

It's hard and sad because it's supposed to be. The White Ribbon is a picture of the secular human heart in a brave new world, free of any miraculous intervention. It's not easy to watch; you desire to hope for something more. But nothing good awaits these characters. Even if they live to figure out the mystery of the village crimes, there's a greater threat lingering on the horizon.

Haneke reminded us in a recent interview that God was declared dead over 100 years ago. The White Ribbon is like a welcome sign to reality when belief has been left behind.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I like to respond to comments. If you keep it relatively clean and respectful, and use your name or any name outside of "Anonymous," I will be much more apt to respond. Spam or stupidity is mine to delete at will. Thanks.