Saturday, April 30, 2011

The Cyclist. (1987) Mohsen Makhmalbaf

As soon as you pop in KINO's "Kimstim" DVD of The Cyclist, you get a warbled sound on the Menu, not unlike an old warped vinyl record, needle dragging across the lines on a turntable where the music feels not only dated but like it needs a shot of Pepto Bismol. I first saw this film on one of the most beat up VHS tapes one can encounter, from the barely discernible exterior title to the scratched and mangled tape inside, so this was a perfect way to revisit the film, which I recently did, and once again I was enthralled.

The Cyclist, a 79 minute Iranian film from 1987, is Makhmalbaf's retelling of an event he witnessed in childhood, but while the story is personal he also opts for it to be told in a social and somewhat political manner. It's about an Afghan refugee named Nasim, whose wife is dying and needs an extended stay in the hospital. A former bicycling champion in his home country, Nasim is now broke and has to figure out a way to pay for her health care. The work he is doing barely pays the bills they already have. He meets a gangster type who makes a living placing bets. He urges the desperate Nasim to involve himself in a wager that he can ride his bike for seven days straight. The event will be promoted for all to see.

The film didn't make the cut on our Top 100 for this year, but placed at number 50 on our list from 2010. After recently seeing Certified Copy (which I blogged Here) and hearing quite a bit of discussion about Close-Up over the years at A&F (a film which is partially based on The Cyclist and holds its position on our current list), I decided to revisit The Cyclist before diving into and blogging Close-Up, which I'll be aiming to write about tomorrow. The former is generally known as paving the way for the latter, Close-Up being the critically recognized film. What I had forgotten is what a great movie The Cyclist still is.

The film is a love story at heart. It's about the lengths Nasim goes to in order to save the spouse he loves. It is a hyper-expressionist film that in some ways hearkens back to the best of Murnau - the passion dramatically expressed in silent cinema is very similar to the feel of The Cyclist. The cinematography is also excellent as it captures all the drama on display, the drama being the hope-filled enjoyable kind. Elements of the downtrodden are certainly present, but the story itself is exciting and just plain fun.

Watching Nasim as he bicycles to save his wife's life, watching him sweat and nearly fall, watching him evade people and objects thrown in his path, in a state somewhere between utter exhaustion and the dream state of a fever, is a one man sporting event akin to the 15 rounds of boxing in the original Rocky. A big difference being that the "punches" here are mental and emotional, as well as physical, as he rides round and round in circles. His thoughts race back to his love in a hospital bed, his heart aches to save her and he knows this is the only way.

The crowds show up, growing exponentially each day. Tickets are sold. The gamblers and the feel of crime is a constant shadow over the event. Government officials see the display as a kind of threat. Vendors and palm readers and an ambulance are just within reach... Nasim splashes buckets of water on his face to keep from falling asleep and falling off his bike. Riots break out around him, nearly knocking him over as he bikes through a crowd of angry protesters. There is a referee constantly present, and many gambling over the event. Cheating with attempts to knock him off the bike becomes normal life for Nasim to deal with.

He eats on the bike. He drinks on the bike. He pees on the bike. He carries his son on the bike. He yawns and falls asleep and is awakened by the crowd on his bike. He even takes a phone call on his bike. He grows faint and his vision goes blurry; he thinks of his wife and saves himself from total collapse. He sweats and weeps and gets a cold and freezes at night. All of these things he does on his bike. He dreams that he's asleep while still awake and riding his bike.

Amidst the crowd of money-grubbing vendors and gamblers and those just there to be entertained, there are quite a few acts of friendship and kindness toward Nasim. There are acts of grace that is the kind of charm Iranian cinema is known for. And the final act is spectacular. This is a film that carries its weight in hope.

The soundtrack of the DVD is a little warbly, but not as warbly as the Menu might lead you to believe, and I think it actually adds to the charm of the tale. The transfer ain't so great but absolutely worth wading through for the story itself. This is a film where story transcends form, that is, the form of the transfer and not the film itself.

As more and more Americans find it difficult to navigate the health care system, and as employment continues to be replaced by uninsured jobs for the "temp" worker, this film becomes more relevant than it was at the time of its release. The lengths one goes to in finding a job and getting insured, or what one would do to save a loved one whose health is jeopardized by inflated health care costs, are issues of greater prevalence every day. America in 1987 wasn't nearly as close to Iran in 1987 as is the 2011 version of the American dream.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

The Mirror. (1975) Andrei Tarkovsky

Over the past week or so, I've been studying what is commonly referred to as Tarkovsky's most personal film, The Mirror.

I say "studying" because I've gone back since my first viewing and watched bits and pieces of it here and there -- thank God for the DVD! -- and read quite a bit about this fascinating film on various blogs around the web. Somewhere in the house I've got a copy of Tarkovsky's book, Sculpting in Time. I wonder if that might be a good reference for carving out an understanding of this film, too. The montage, which he often referred to in the book as the "rhythm" of a film, seems very different in The Mirror than in the other Tarkovskys I've seen. (Solaris, Andrei Rublev, Offret and Stalker.)

And, for many, that's a good thing. One of the largest complaints about those other films is in regard to their deliberate, snail-like pacing. In a sort of hindsight reaction to the rapid cuts of his filmic forefather Eisenstein (in The Odessa Staircase, for instance), Tarkovsky is well known for long, drawn out scenes and an extremely slow tempo where a shot can reach eternal proportions and a cut can take several minutes to get to. It's either mesmerizing or frustrating depending on the viewer. Tarkovsky felt that the cut was a false reality, and in his attempt at truth, an ideal he held in the highest regard, he widely employed the long take, a sometimes agonizing approach in which emotions are reached not through the manipulation of the edit but rather the truth of the reality depicted (perhaps most famous in this three minute railroad sequence from Stalker).

And yet I can use a word like "agonizing" as easily as I can use words like "enriching" and "rewarding." I really appreciate Tarkovsky's ability to slow down our pulse, giving us space to think and breathe, helping us seep gently into the layers of one of his films. In the digital age we rarely have a chance to consider reality, and the rapid edit goes hand in hand with a lot of CGI. I've sat and counted 1.2 seconds between edits in many frustrating movie houses. Our culture despises patience but it is patience that always pays off. Tarkovsky created films that teach from their image as well as their philosophy.

One of the things all Tarkovskys have in common with each other is that they are a complete visual euphoria. And while Tarkovsky seemed to steer clear of overt metaphor, the images conveyed in his films constantly point to an unknown Creator. "Through the image is sustained an awareness of the infinite: the eternal within the finite, the spiritual within matter, the limitless given form," he has said. The Mirror is certainly no different in this regard. From a bottle tipping from a table for an unseen reason to several flurrying portions of mystical montage, viewers are transported into a greater awareness of life; there is more than just the physical that meets the eye. Tarkovsky employs tricks in the mis-en-scène as well as tricks in scene blocking and the lensing. It's a visual feast -- not scopophilic, but transitory.

It is for this reason one can make it through The Mirror for the first time. If it weren't for these visual flourishes, the film would be lost on us at once. The Mirror is visual poetry, with autobiographical details that won't ever be fully understood by anyone in the audience. This is why people who love the film say they've seen it ten, perhaps fifteen times, and that they get something new out of it every time they sit and watch. This is Tarkovsky on Tarkovsky, full stream of consciousness, and he gets away with it because of the film's Eye.

It has something to do with three periods of time: pre-World War II, the actual time of war itself, and the Russian recovery from the war all the way into the sixties. There is nothing chronological about the way these periods are rendered. They pop up sporadically at will. Archived film, newsreels, also pop up wherever they want, some of the grainy black and white images astounding. The most memorable images being soldiers in a time of war, or a man on a chair in the air on one of the very first flights in a balloon.

The film follows a few main characters that seem to stand in for Tarkovsky as a boy, with his mother and lover always close by (lead actress Margarita Terekhova playing both roles). We see into all their lives in a non-linear story in which random moments of their existence play out. The time the barn burned down and all they could do was watch. The time the kids got in trouble in their battle training. The time that lady came over instead of mom coming home. The time the water ran out in the shower. A good portion, if autobiographical, is also a jaunt into childhood memories, ones that won't be forgotten because they're preserved on film forever.

The film is punctuated by philosophical poetry, the narrator asking the important questions about life. Wind and nature are a constant source of reflection as if we should meditate on these elements daily. Quite a few times I was reminded that my favorite director Lars von Trier dedicated his movie Antichrist to Andrei Tarkovsky. Going back to The Mirror, you can see where von Trier borrows, how he playfully uses the methods that have been passed down to him from the Russian master. And you can see why he holds the Russian master in highest esteem.

If you're not prepared to simply bask in the visual elements, I think The Mirror can be a frustrating trip for a first-time viewer. If you're not at all familiar with Tarkovsky's work, it will undoubtedly be a point of frustration. While the film is surreal, I still can't put meaning to it the way I can with a film like, say, Eraserhead, where I have loved for years to dip into the tiny details and drag the symbolism out of the film. Eraserhead remains in my mind a surreal work of art from which I continue to take away personal reflections.

So The Mirror, to me, is an incredible achievement, an expansive and majestic work of art, and yet I cannot derive much meaning from it in my first few days with it. This is Tarkovsky's own reflection and perhaps only he fully understands it. But it reminded me of the greatness of his entire body of work, and I find myself in the wake of The Mirror wanting to revisit the four I've seen very soon. And perhaps I'll add a few I haven't seen to the list.

Saturday, April 23, 2011

Marwencol. (2010) Jeff Malmberg

Story and Imagination as forces for healing and redemption are greatly displayed in this perfectly paced doc about a 38 year-old man and his Barbies.

After being attacked and dragged outside a bar where he was beaten and kicked until laying on the ground unconscious, Mark Hogancamp spent 40 days in a hospital, the first nine in a coma after which he relearned how to eat, write and how to walk. He literally had his brains bashed in in that bar fight, losing all of his memory after the attack. He woke up not remembering a thing about his past - about his life, about his talents in drawing, his alcoholism or his ex-wife. Going back through his journals to discover himself he found a horror story of a life gone awry; realizing what he had become but what he still couldn't recall felt like something from a Stephen King novel.

The drawings in the journals are just as horrifying as the words he reads. Pictures of Mark clinging desperately to two large letters reading "AA," and other drawings of himself being tortured by his drink. There is no doubt he was lost, enslaved. He was desperate, and according to his drawings and words, he knew it.

Unable to physically draw due to the nature of his post-attack brain function, and unable to mentally draw on any memories in his past, Mark, ever the artist, turns his back yard into a set for miniatures where WWII heroes and SS soldiers, Nazis and Barbies form a town in his brain called Marwencol. It is here that Mark's imagination replaces his memory, filling in the gaps of his memory banks for a therapeutic session of storybook photography. Many of the dolls are based on real-life people in Mark's life, in fact the name of the town stands for Mark, Wendy and Colleen, the latter two being the first girls he had a crush on in returning to his "second half of life."

The photos he comes up with are amazing.

Mark takes these miniatures and creates grandiose stories, stories of survival, war and love - drama queen stories where the girl drops her man for Steve McQueen, stories of bloodshed and tears and riots and revolts. He's front and center in most of the tales, his own miniature alter-ego bumping up daily with the town's folk. The women he's liked in real life are present too. He hugs and kisses the dolls sometimes. It's a little bit creepy.

The general underlying theme of the story is that Marwencol is a town striving for peace, that Mark and the soldiers and Barbies live there together and they'll fight off any Nazis that plot to take over. Marwencol is always under the gun. The forces are always out there, ever looming over the town for their chance to seize it at any moment. It's up to Mark and his friends and the 27 Barbies to make sure Marwencol is safe for today and tomorrow.

The town's battles are an obvious stand-in for the trauma Mark has experienced in real life. Likewise the drama between some of the Barbies and their boyfriends seems to function as a gateway to Mark's loneliness and isolation. The film is quite rewarding as Mark opens up; we get to see his thought process as he builds sets and photos it all. Thousands of photos are stored away, photos that will later be dragged out when Mark is invited to a gallery in New York. Perhaps with these artists he'll finally find a place to fit in.

Director Malmberg does a brilliant job in simply staying out of the way. We see the story develop from Mark's initial beating to the hospital stay to the design of the sets and the photographing of Marwencol, all the way to the gallery in New York where Mark's town and its stories hit the public. There are a couple of surprises along the way, including the reason for the beating. And it's a shocker. It's one of those things you might need a moment to think about, and when you really consider all you've seen it makes sense, but then, hmm, it doesn't.

Like Stevie or Prodigal Sons, or maybe a not so violent but still artistically relevant Tarnation, Marwencol is a documentary that studies one person, his unique and beautiful mind, his actions and a path that is only his. It's insightful to see into the mind of someone else, to take a break from yourself and relish another. In Marwencol, it's like studying about that guy on the street you've seen every day for years. It's an interesting trip into the mind of a man wrestling with fallout and transcending his creation.

Monday, April 18, 2011

Paris, Texas. (1984) Wim Wenders

Weary, dizzy, and bone-dry dehydrated, a catatonic sunburned bearded stranger steps out of the Texas desert into a bar. He's been wandering in the scorching sun, apparently going nowhere, headed for a destination perhaps long forgotten. But for what he needs now, alcohol will not suffice. If he can't find some water in this dingy little dive there's really no question that he will die.

He stumbles across the darkened room to an ice box to quench his thirst. His dry, dusty mouth is quickly relieved in crunching the cubes, but immediately upon swallowing his body falters. He crashes to the floor and passes out. Upon waking, he's under the care of a cigar toting German doctor who finds his ID and makes a phone call to his brother in L.A. We learn he's been missing four years. His brother comes to collect him, but by the time he gets there, the wanderer is gone, traversing the desert terrain yet again.

Working with only the first half of a full script and shooting in chronological order, Wim Wenders, in these opening scenes where a man tries to help his drifting brother, draws us patiently into all the themes that will gently unfold in this story of a man who trails back to his lost son. It's the Prodigal dad returning home from a mysterious wasteland of the heart. Then again, it's the Prodigal husband who recklessly wandered away, leaving the ruins of a relationship in the dust. The desert can be a physical place, but it can symbolize an interior condition, too.

Travis, the bearded wanderer, will soon be shaving and meeting his eight year-old son Hunter for the first time since the boy was four. What happened during those years is anyone's guess, but Hunter has been staying with his uncle, the brother now saving Travis, meaning Travis will soon be reintroduced to his boy. But picture an eight year-old who already has a daddy and mommy, being introduced to a man that they're both hailing as long, lost dad.

In a cute scene capturing eight year-old Hunter trying to come to terms with all this, he explains to a friend how he now has two dads. "Who is that guy? You know him?" asks his friend. Hunter: "Yeah, he's my father's brother... No, they're both brothers... No, they're both -- they're both fathers... Aw, just forget it."

It will take some time for the two to fully bond, and there is still the question of the past four years, the desert wandering, and the missing mom. What happened to her? What actually happened to them? What is that awful event that Travis won't talk about that brought them to the point of losing their son? The bonding continues, and the two begin working toward some answers, but not before we meet a screaming, mad prophet standing over a highway insulting the traffic flowing below. In one of the greatest scenes in the film, this soapbox traffic-hating apocalyptist comes from out of nowhere, like a fire-breathing turn-or-burn preacher on acid. His sermon seems to launch Travis and son on a road trip to their source, and Travis will finally give his story as a reflection in an isolated confessional. There are believable, tender, heart wrenching scenes at the end of this story. Bring some Kleenex. You have been forewarned.

Paris, Texas functions as a place where land is owned, but it is ground no one in the story has been on. The idea reminds me of the words of another Wenders title, Faraway, So Close -- We're not always meant to be together, and some mistakes can't be undone. Restoration isn't always possible; we can only do our best with what we have, living daily to take care of the present. Paris, Texas feels more like an idea than a title or a location or a purchase of land. The film of this title is like a longing for home, but perhaps it's a place we can't go.

Born to Be Wild. (2011) David Lickley

This is an IMAX 3D film currently in theaters. Narrated by Morgan Freeman, it is in the wild but no penguins this time. Instead we have baby elephants in Kenya and orphaned orangutans taken care of by humans in the rainforests of Borneo.

This is easily the deepest, richest 3D experience I've seen. Yes, that includes Avatar -- because this is reality, and you can see these lands for miles. Truly an inspiring work, I felt like I had visited these countries through this masterfully made nature film.

I know Herzog has a documentary coming out in this format (not sure if it is supposed to go on IMAX screens), but I hadn't really considered how well suited 3D is for a documentary feature. Here, it really drives home a wealth of visuals in a world that escapes most of us.

Certainly a rewarding little info-piece of a film, but I didn't walk away without reservations for recommending it, mostly due to its length and the cost to get into the theater. More Here.

Saturday, April 16, 2011

Certified Copy. (2011) Abbas Kiarostami

Hauntingly beautiful with devastating dialogue, Kiarostami's first film shot far from his original home in Iran is so vibrant and full of life -- its foils, its struggles, its yearnings -- that it needs to be seen more than once to fully digest everything it launches at the viewer. It's THE ONE the film buff waits for as he wades through hundreds to finally arrive here. It's THE ONE film buffs will talk about years from now, and average moviegoers won't have seen.

It was seen by many at Cannes last year, and it was there that Juliette Binoche, amidst applause and mumbled groans at the predictability of it all, took home the Best Actress award for her role, the latest in an endless amount of roles the committed star was born to play. She carries the film like it will live or die on her shoulders, her every facial gesture as amazing as always, and though I've said it before I'll gladly say it again: she has taken her talents to an amazing new level. To see Binoche in practically any film is to see the Best of the Best, and as the years go on she ages perfectly with time. With time, she simply ascends.

IMDB reports that her character in the film is named Elle, but I don't know where they got that. It's not in the film I saw. For the purposes of Kiarostami's original idea for Certified Copy, I'll simply call her "She."

We find She with her skateboarder-looking teenager at a book signing in Tuscany. The esteemed author is British middle-aged James Miller (William Shimell, carried in the film by La Binoche) who has authored "Certified Copy," a book about artifice and art. As the two take a jaunt around the outskirts of Tuscany, the film begins to model the ideas of the book in its majestic cinematography, in the locations the two choose to visit, and in the dialogue and interaction between the characters themselves, whose relationship is completely transformed (think: the shifts in perspective of Persona, but replacing the lesbian tendencies with marriage struggles). She and James discuss life, art, artifice, outright fraud, aging, parenthood, problems and the frustrations they immediately have with one another. They discuss these things like they're going to fall in love or punch each other at any moment. It's as if they've known each other for years, caught up in romance and intolerance, and as such the film feels like a more original, more masterful Before Sunrise or a Tuscany-replacing-Tokyo Lost in Translation. The dialogue and chemistry between She and James is of the highest calibre you will find in a film. Binoche can give you eight emotions in eleven seconds, every single one of them tearing a hole in your heart.

Kiarostami is the master behind the lens, taking us into mirrors, windshields, alleyways and marriage ceremonies. He shifts the film's perspective as our persectives on the two leads shift. There's a playful sense that we're being tormented by an illusion, a reflection, or a glance in the mirror at ourselves. Every shot in the film is poetry, a walk through Tuscany aiding all the beauty found here.

As they continue their walk and as they talk they shed layers, most notably demonstrated in the removal of Binoche's bra in a church bathroom. I know that last thought looks a little weird when you read it -- it is as tasteful and perfect a metaphor as anything in Haneke's Code Unknown. (Which is yet another incredible film rendering the capabilities of Binoche's codes.) There's a shift in the way She begins looking at him, and a shift in the way we look at her. She is more than a walk around Tuscany. The role she's now taken is fully engaging.

The film ends with church bells ringing, an interesting choice for an Iranian filmmaker set free of the constraints of Iran. There's also a final choice that is perhaps left open to interpretation, but most will interpret as full tragedy. It is easily one of the most gripping finales you will see on a screen this year, and yet no words are spoken, a decision is made, and that's it. The bells ring out through the credits.

I've seen the ending twice, both times with small audiences, and I was amazed that no one could get up to leave the theater. They sat through the entire credits sequence, which is not in English, bells continuing to ring out, as if they'd just witnessed an honest, raw, devastating choice, like a couple's split that has left a child whiplashed, wounded by their delusions, their (in)sincerity about themselves, and the nature of greed and how it affects all parties in a Union.

Thursday, April 14, 2011

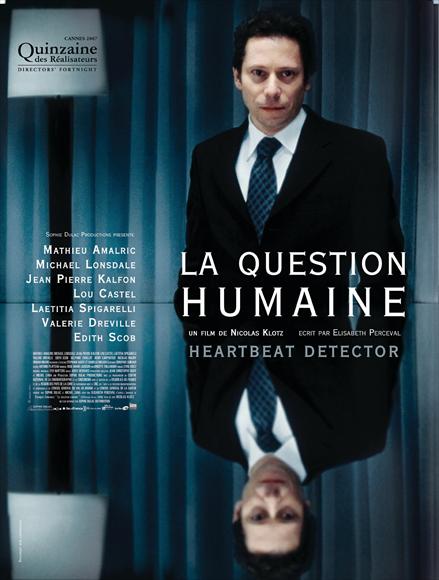

Heartbeat Detector. (2007) Nicolas Klotz

It begins with Simon Kessler, the human resources psychologist, who is asked to get to better know his company's alcoholic and despondent CEO, Mathias Jüst -- to monitor his behavior and report back to Karl Rose, the vice president. Simon gets the novel idea to begin an orchestral program that was attempted a few years back with the goal of getting Jüst involved on his violin playing with any blue or white collar worker willing to be involved.

The film plummets some ground that hit me personally pretty hard. There's a political back text that becomes front and center in the film's second half that anyone who reviews the film will talk about, that of European disillusion even sixty years after WWII, and how corporations and their employees still have to stare those days in the face and work in the midst of it. I found that aspect interesting, very much so, but it's not what got my heart pumping. What got to me was director Nicolas Klotz's ability to place all forms of music in the heart of the film, a music we very quickly learn that neither Jüst nor Simon can relate to. Because they can't relate to much of anything or anyone, really. It's amazing how much communication it takes to put the right pieces in place to run a company, and how you can create wealth like moving chess pieces on a business platform -- you can seemingly have it all and still be an unrelatable miserable grouch who has slipped through the cracks -- you've forgotten the importance of breaking through your own isolated humanity, that it is misery to be trapped and alone, and yet even those in business at the top of their game can fall into this horrible life pattern.

Jüst cannot gain even a simple pleasure from listening to music he created in the past. He says it physically pains him, and we see it bring him to the point of tears. As he slowly descends into a pit of isolation we see Simon trying to put the social program together for employees who don't really want to have a part of it. But it doesn't end at the workplace for Simon. Klotz gives us so many chances to peek into the life of the company psychologist who attends raves and drinks and dances the night away and has a girlfriend that could beautifully sing to him if only he'd stop and listen and quit trying to bed her instead. The music that permeates the film -- from classical to latin flavored to house and then simple soundtrack filler -- can be heard by any viewer as touching in some way. One of the film's secondary ideas, the one that got to me, was watching this character in the midst of it all, unable to join in the song of life because he is trapped in his own isolation. His heart won't thump to the vibrant sounds around him. It's sad that there can be such beauty around us every day, and many times we just let it go by, barely noticed, the art we can't connect with because we're so revved up in consuming it.

Then again, maybe I just liked that theme because I spent seventeen years in music that took me all over the globe, and I haven't touched an instrument in months.

The film is on our Top 100 at A&F, probably more for the political and spiritual text I mentioned, and there's been some great writing done on it already. We've been discussing the film Here (and some of us Here), and I highly recommend my friend Michael Leary's review Here, and my friend Darren Hughes's very visual review Here. It's always a joy to read any of these guys. When they get their thoughts down to words it is a stirring, emotive experience.

Thursday, April 7, 2011

The Searchers. (1956) John Ford

I had a poor reaction to this film but I've been talked into seeing that my reaction might have been steered that direction -- that perhaps the whole point of it is having that bad reaction. So, I guess, I can respect that, but it's not a fun experience. I've been told I'm not alone in that initial response, so perhaps I'll try it again in a few years. But about thirty minutes in, the dialogue and acting become so cliched that I'm simply assuming (for now) that I don't get it and this film is not to my tastes. That's not to say that tastes can't change over time. I think they do. But for now, my response to The Searchers is pretty much blechth.

The Peter Bogdanovich commentary on the DVD does help explain all the love. It's simply not a love I currently share.

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

Get Low. (2010) Aaron Schneider

Get Low, a reference to a person going six feet under, is built partially from an event in the 1930s where a backwoods codger planned his own living funeral, mythologized in Schneider's film to probe the meaning of being redeemed.

And what does it mean to be redeemed?

I use the term purely in the Christian sense, because the film so closely aligns itself with that worldview. Many films have plots and characters which draw on themes of "redemption". While misguided about redemption from the standpoint of southern faith, the crotchety old man played by Robert Duvall in Get Low is still looking, in the Christian sense, to be redeemed.

For forty years Felix Bush (Duvall) has hidden himself away in his cabin deep in the woods in Tennessee, a mysterious geezer-hermit with all kinds of legends that the locals just love to chew on. He's like the neighbor lady I saw as a kid who used the hose to water her driveway and gave away soup on Halloween. We were never quite sure what her story was, but man, could we make some up.

Stylin' on a stagecoach, Bush heads into town one day, shotgun in hand, to visit the fellows at the funeral home. He tells them (one of which is Bill Murray and his oh-so-30s moustache) that he wants to plan a funeral. His funeral. Right now, while he's still alive. He wants to invite all the townspeople to tell a few of the tales about him, live it up, party on, and celebrate his demise. He's putting his land in a lottery to be collected at the time of his death, the raffle winner being announced at the funeral.

After Mr. Bush gets a decent haircut and makes the announcement over the radio, the event turns into the talk of the town. In such a remote setting, it will surely be the event of the year. Maybe the event of a quite a few years.

But it is apparently more than a fun get-together for nutty old Mr. Bush. It seems he's got something he wants to talk about at the big show. Something deep and dark that he's buried in those woods, hidden away for the past forty years. Rumors around town are that he killed a man, maybe two or three. We meet Sissy Spacek as an old flame: "We had a go," he wryly tells the funeral guys. There's something about this relationship that is a mystery. The two come from a place where grunts and glances are as good as any words. The spaces between their words are filled with a background we can only guess at.

This is one of those stories where this is about that. We might be looking at the tall tale of a kooky backwoods flea scratcher, but the film is actually about preparing your heart for what's later by clearing your schedule and making amends now -- and if you can't make amends, at least setting some stories straight. The heart of Get Low is as good as anything in the story, and it's a reason I look forward to seeing it again very soon. (If I had seen it before the end of last year, it would have given me serious pause in trying to pick a Top Ten without it being somewhere on the list.)

Since I've borrowed the idea of this being about that from Rob Bell, I might as well go ahead and say that I just finished reading "Love Wins" (soon twice, and I'll most likely blog the book here soon), and that the timing on reading the book and seeing the film together is about as satisfying an arts experience as one can get. The two would make a great double billing. First read "Love Wins," and then see Get Low. Then ask yourself:

Did Mr. Bush repent to God? Has he atoned for his sins? Is repenting to your fellow man enough? Isn't it enough in some Christian circles? Are words really EVER enough? Is the action of the words in confession to a thousand townsfolk any better than the action of building a house of worship years ago? If someone somehow stumbles on truth and amazingly gets the actions right, coming from a pure and contrite heart, but doesn't actually get their words to the right source, has that person really made atonement for their sin? Did King David have a Jesus to repent to? Did Cain get to pray the "sinner's prayer"?

We have a character in Mr. Bush that's desperate to make peace in the world before he moves on to the next one, whatever that is. The question is more about having God's peace correct a long standing situation here and now then it is worrying about the fires of hell. Guilt has eaten away at the crotchety old man for forty years, and he needs to out this thing now, and not just for himself. It's a character doing the right human thing, the right, honorable Christian thing, while not necessarily in the confines of Christianity. That said, there seems to be an understanding that what he is doing, he is doing for peace, for reconciliation. He lives surrounded by God's beauty all the time. These backwoods types breathe God's air every day. He has watched the land around him every day for forty years and knows that the corrections he needs to make in the flesh have vast, earth shattering, heavenly implications.

This is a gorgeous film, with a wonderful, subdued soundtrack. Gosh, that bluegrass music lingering quietly in the background is fun. My grandpa was a bluegrass player in Mississippi. This stuff gets to me on a personal basis as a part of the family tree I've always enjoyed. I was a musician on the rock road for many years, but the roots of bluegrass must be where it all started for me. Somewhere inside this boy who loves the big cities and crowded night life is a backwoods red dirt finger-picker just longing for a banjo at heart.

Sunday, April 3, 2011

The Gospel According to St. Matthew. (1964)

Pier Paolo Pasolini

I'll preface my reaction to Pasolini's Gospel rendition by stating that I'm already a huge fan of this story, have been my whole life, which is probably obvious if know me or have read something here before. The Gospel is a story I'm willing to base my life on, but at times I feel it's a cosmic gamble of sorts -- one plus one rather seems to equal two, so in the grand scheme of things the Story makes the most sense. I don't deal well with the collective baggage of contemporary Christianity, but I like the Christ story. I hope that such a beautiful thing can also be the Truth (capital "T"), but I'm willing to follow this narrative understanding of the Universe as opposed to quite a few bullet- and power-point sermons blithely spoken across the land on many Sunday morning gatherings in the US.

I'm not always a fan of the Gospel story when it is portrayed in film. I can't say it's usually done well in this format. I am, however, a huge fan of at least three Jesus films which have really sunk themselves into the core of my understanding of life: The Miracle Maker, which I wrote about Here and is #26 on this year's Top 100, is the first one that comes to mind. Artistically created with stop-motion puppetry animation, it is that rare version of the Gospel that appeals to both young and old, a perfect introduction for children that's also suited to the tastes of appreciative adults.

I also have a tremendous amount of respect for The Passion of the Christ, Mel Gibson's bloody, raw, visceral and some say anti-Semitic rendering of Christ's final few hours (and a film I scooped years ago in putting up the first review on the net), and The Last Temptation of Christ, a fictional psychological retelling of the Gospel which got inside the head of Jesus to figure out how he managed mentally as God lodged in human flesh -- the struggle ingrained in a psyche that is fully man and yet fully God, Jehova wrapped in the skin of original sin.

These are the three that have stuck with me so far. Many more that I can't name come to mind as films that I'd rather not remember -- usually low budget features made by serious minded but artistically defunct evangelicals. My friend Matt, who is an expert in this field, would probably recommend quite a few solid films that I've never even heard of. He specializes in Jesus films and blogs about them Here. It is through his recommendation, and quite a few others at the A&F community that I finally took a chance on The Gospel According to St. Matthew.

This is not the family friendly introduction to Jesus in The Miracle Maker, nor is it the deeply probing psychological profile study of The Last Temptation of Christ. Neither is it anything as violent and visually gripping as The Passion of the Christ -- the grande finale of the crucifixion scene itself is rendered as bloodless in Pasolini's film. It is, however, a version that I think stands out from the rest. Quite a few unforgettable moments bring visuals to scenes that have lived in the heads of Christians for years. But the film has a slow, meditative, challenging nature to it, and it is old, which may present problems to contemporary viewers.

I'm no film scholar, so it would be hard for me to relate what the film meant to anyone who saw it in the mid-sixties, but viewing it now is in some moments like taking in a large scale art school project. Long, static scenes of silence with a roving camera in close-up travels from face to face in large gatherings of people. Shots like this are held for excruciating lengths of time, which can lead one into a sleepy mode of movie watching. I have several friends that love the film, who say they fell asleep the first time they tried to view it.

It's also shot in black and white, captured mostly outdoors, and at times feels like Ingmar Bergman got involved with the project, though this is a larger scale film than you'd find in Bergman's productions. But the Bergman mention is apt -- it gets at what I was trying to describe earlier when I mentioned art school.

None of this is to say it is a bad film. It isn't. It's an epic, sprawling, majestic piece of cinema. But let this serve as a warning for what you're getting into when you sit down with The Gospel According to St. Matthew. There are moments that will surely try any reasonable viewer's patience, combined with moments which shed a unique light on the story of Christ, perhaps not present or told like this in other Gospel films.

There are more than a few haunting moments: the visit from the Magi brings about Herod the Great's Massacre of the Innocents, depicted here as soldiers chasing down scores of women and children to spear and cut the heads off of their newborn or very young sons; Jesus on his knees praying and fasting in the desert and wrestling with the chaos of temptation over control of the world; John the Baptist baptising Jesus before being imprisoned and having his head laid out on a literal chopping block; and of course the Sermon on the Mount, which I believe this film is known for, laid out in a montage which takes place over several days and nights and locations -- suggesting the sermons were steadily repeated over time.

After the calling of his disciples, a grotesque figure approaches them, a leper asking Jesus for healing. Only words are spoken in this amazing, miraculous scene where the healing is shown as instantaneous, and it is perfect. It's stunning to be suddenly presented with a normal looking man after seeing him at first in his ugly deformed state. As would be the usual, Jesus asks him not to tell anyone, but the man, of course, immediately attracts a large, questioning and excited crowd.

Christ's Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem on the back of a lowly mule is another moment that absolutely mesmerizes. There must have been hundreds of extras. They're all waving palm branches as they should, and throwing down garments for the path of their approaching King. The expectation and the excitement is that Christ will soon be setting them free from a life under Roman rule. There is joyous fervor here, electricity fills the air. They are intoxicated at the thought of their oppressor finally "getting theirs", though many in the crowd will turn on Jesus in just a few days. The Triumphal Entry in this version leads Christ straight into the temple, where the greatest confrontation yet is going to take place.

This is the scene where Jesus is the liberator of the religiously oppressed, the spiritually abused. His roughback moment of turning over tables in the temple is a pivotal, highly charged moment. He doesn't stop and create a whip first -- rendered here, it is a rash, quick moment of righteous anger. He screams that the temple is made for worship, now being made into a den of thieves, and immediately all of the scribes and Pharisees see what he's done and the commoners rush into the house of worship. The children immediately exalt him, and it is perhaps here where we see his glowing smile in the film, a moment of the sheer satisfaction at what he's just done and the pleasure he gets from the mouths of children. They are waving their palm branches and shouting, "Hosanna to the Son of David!" It is clear in Pasolini's version -- and it seems to make a lot of sense when you think about it -- that this is the final blow in a conspiracy surrounding his approaching imminent death. The scribes and Pharisees can't believe their eyes at what he's just done on their turf. Their plot to have him dead and gone is ratcheted up another notch. Things will not be the same from this point forward.

The Jesus of Pasolini's film is serious, solemn. Aside from the satisfaction with the children in the temple, he really doesn't smile very much. This Jesus isn't the hippie rocker messiah of Jesus Christ, Superstar. He doesn't smile at his own parables or laugh when he teaches, as he did in other filmed versions of the story. He doesn't seem amused with himself or his stories at all. This is a Jesus who clearly understands the solemn nature of his messianic mission. He knows his role in the world, he knows the sacrifice he is here to make. He knows the political forces he is in conflict with and can see to the core of their religious hypocrisy. He calls them out on it in quite a few searing scenes where he preaches outside their walls and windows, blasting them as vipers ensconced in the allure of religious power and wealth. (As an aside, the Jesus of Pasolini's film, actor Enrique Irazoqui, did stop in for a few brief appearances on the A&F forum beginning Here.)

The crucifixion, as I've said, is bloodless, but the power of Christ even from the cross is onscreen. As Jesus screams in agony that God has forsaken him, an earthquake rockets through the city, pummeling several buildings along the way. We don't see the temple vale torn in two, but can surmise that it happened in this moment. And of course, there's a resurrection (and an assumed ascension), unique to a film created by a Marxist-atheist, showing that Pasolini really was interested in the story itself, and the movement that ensued and changed the world.

One of the other things I find interesting is that if Pasolini was an atheist who read the four Canonical gospels and suddenly found himself interested in the Jesus story, why does he include the prophesies that authenticate it as Reality? The wise men from the east telling Herod that the baby will be born in Bethlehem; a narrator that points out the prophesy "Out of Egypt I have called my Son"; Jesus in many moments showing the parallels between the words of Old Testament prophets and the actions surrounding his life. Prophesy and its fulfilment is loaded into the film, illustrating the director's poetic sensibilities in front of his Marxist-atheist worldview. I wonder if the Story had any greater impact on him, or any of the other actors or workers involved, than simply the making of a great Italian art epic.

Overall, the film is solid, perhaps a masterpiece in its day, but too artsy and neo-realist for today's average movie goer. The kid that loves Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (these poor gamer teens just don't know any better) will find the film dry, tedious, old and "boring." I can't say the same. The further I got into it, the deeper and richer the film became for me, to where at the end I could only admit that it is a "classic." But as far as the Jesus story goes for contemporary audiences, I'd still list the other films I mentioned before this.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)